Playing with Beginnings, Middles, and Ends

Andrew Pyper

April 16, 2013

I have found that many writers—both those just starting out and those I feel ought to know better—are allergic to the very idea of outlines. The criticisms (or prejudices, as a good number of those who bash outlines have never tried them) tend to focus on the loss of spontaneity or sense of play that results from thinking too much about a writing project in advance.

My answer to them is that outline-making in itself is an opportunity for wild and boundless creativity. Far from straitjacketing the story to a “formula,” it allows you to conceive and re-conceive an idea without the penalty of wasting your time writing it out only to find your enthusiasm exhausted, caught in a dead end with no way out.

Outlines have many benefits I could trumpet, but for the purposes of this exercise, I will focus on only one: the order of things. Specifically, the way we arrange the events of a story will largely determine a reader’s level of engagement (and our own). Playing with beginnings, middles and ends is one way to build suspense, or create surprises, or deepen emotional involvement, where telling it in a straight chronological sequence might not.

The Exercise

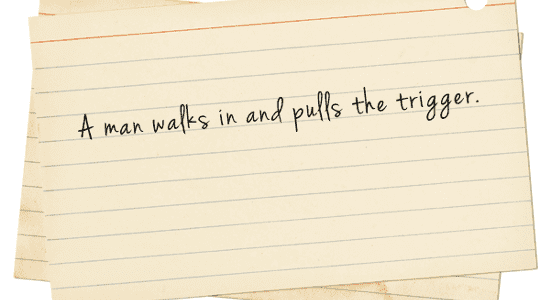

Take an Idea for a Story. It could be a short story, a comic, an epic trilogy—the genre or length or form doesn’t matter. Now take the time to write out the beats of the story on index cards, each card limited to a single turn or pivotal scene or even smaller nuggets such as a joke or bit of dialogue you think is worthwhile. Don’t rush—really spill out all the thoughts and ideas the story needs, the sparks it inspires. Try to answer the question “What happens next? ” every time it arises, along with “How did we get here? ”

When you’ve drained out the entirety of your brain, spread the index cards out over a table and just scan them for a time. Then start putting them in order. That order doesn’t have to be in a chronological “start” to “finish”—indeed, it probably shouldn’t be. Order the beats and scenes in ways that feel right. Start in the middle. Start at the end. Reveal something a third of the way through that doesn’t make sense, but will make sense two-thirds of the way through. Tell the story backwards.

I’ll bet you’ll find that this exercise—which is really just one way to outline—is involving and useful and fun. You’ll find ways to jump right into the heart of your story that gets around a potentially dull set-up. The main thing is, it will help reveal your own priorities and preferences. Goofing with the order of things will make the story yours.