I recommend the writing exercises I included in The Writer’s Gym, (edited by Eliza Clark, published by Penguin). One is about writing and the other is about editing.

Tell us about yourself.

I write fiction (mainly novels, but sometimes short stories) non-fiction, and I secretly write poems. I’ve published the novels, Matadora, Smoke, and Ten Good Seconds of Silence. I’ve also published a novella for adult literacy learners entitled, Love You to Death. I work freelance as an editor. The first book I edited was the collection Bent on Writing: Contemporary Queer Tales. I also mentor and teach aspiring creative writers across Canada.

When did you realize you had a passion for writing?

I began writing when I could read in English, around the age of 6 or 7. I started with poems, and with creating a library in my bedroom, including using my own cataloguing system for organization. I committed to writing for the first time when I was in grade 4 and there was a competition for the grade 4, 5 and 6 students. When I didn’t win, I was determined to write until someone agreed it was worth reading.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

Writers influence me profoundly, but that influence is mitigated by whatever stage I’m at with my writing and whatever is going on in my stage of life. Right now, I am on a non-fiction bender, and can’t get enough. I’m currently reading a memoir: I Await the Devil’s Coming by Mary MacLane. Before that, I loved An Arab Melancholia. What moves me most is an author’s passion for their subject, and a fresh look at life or the world around them. In my life, the following books have had a major effect on my sense of what is possible on the page: The Little Prince, A Prayer for Owen Meany, the poetry of Garcia Lorca, stories by Edgar Allan Poe, the work of Jeanette Winterson, Wild Dogs by Helen Humphreys, Headhunter by Timothy Findley, and others.

How and when do you find time to write?

Before my daughter was born I wrote every day 9-5, 7 days/week. Some evenings too. For the first 5 years of my daughter’s life, while I was at home with her, I began my writing “day” at 7:30 pm and wrote until 2 am. Now that she’s in school full days, I write for several hours in the middle of the day.

What has been some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced as a writer?

After 15 years living full time as a writer, I would say the two biggest challenges are time and money. They are, of course, related. Finding enough of both to keep going with a project and with paying the bills. After that, it’s isolation. Novels require years behind a desk, on the other side of a window, watching the world go by.

How have you changed as a writer over the years?

When I began my first novel, I had no idea about the hell that could be a writing process. I was fresh, energized and nicely naïve. All good things. Now, I know better so I am pickier about projects going forward, have to know that I will live within them for years, because that’s how long it will take me. Also, now I know each project gets harder, not easier, funnily enough. You’re always chasing your talent, and ambition regardless of how many books are under your belt.

Tell us about yourself.

I lived in China and the U.S. before moving to Canada. I was a freelance journalist for a few years, and recently got a 9-5 job. Even so, I have a constant sense of impermanence, of life in transition.

Tell us about the piece you’ve decided to share.

I wrote this feature on commuter students for The Varsity, my campus newspaper at the University of Toronto. Most at U of T are commuters, and this daily grind often carries over to work life as well. It was so different from how I imagined university growing up. I wondered how this experience was shaping our generation.

When and why did you realize you had a passion for writing?

University is when I really started writing. It was a time when I couldn’t study everything anymore; I had to choose. I originally chose engineering, then decided to quit and major in English and French literature.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

I have many answers to this question, depending on when you catch me.

I often recall the books I read in early childhood. Chinese stories by authors unknown (to me) have stuck. I respect that they don’t hold back on loss, death, or the cruelty of circumstance, or maybe I just remember the most tragic ones.

One of the first English stories I read was “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” I was nine. I can’t remember whether I took to it so keenly because it reflected my reality or whether it subsequently shaped the way I live.

The writings of Zhuangzi, so fluid and so dense, are a later discovery.

What kind of writer do you aspire to be?

When I find writing that is apt, open, seeking, I am transformed. That is the kind of writing I aspire to do.

How and when do you find time to write?

Weekend mornings are the best time to sit down and work. I do write in my head all the time, during commutes or when I’m waiting in line. It’s a good way to feel things out without the pressure of a blank screen.

I know nothing about mining, but am from a mining town, have listened to the men snowball space for eighteen years, cultivate houses and children and four-wheelers in the spun out jade vines of their palms. I think I am a corpse flower with a caustic rafflesia smell, an entire rootless paradise in my mouth.

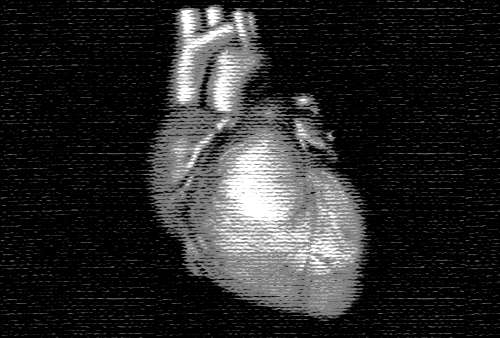

A couple of years ago, I was at a talk by Monique Mojica, a Kuna and Rappahannock actor and playwright who had done a tremendous amount of work building the Indigenous theatre movement in Canada and the US. In this talk, she was talking about Kuna aesthetics and a Kuna editorial process based on the heart. I immediately identified with her teachings, and I started to think about the editing process differently. In Anishinaabeg, our word for heart is de. Our word for truth is debwe, and some of our Elders define truth as the sound of the heart. Monique talked about editing her play using the sound of her heart—to me, this has meant going through my work, line by line and making sure that it resonates with that part of me. Of course it is important to make sure that the story makes sense in all the other ways we usually edit, but for my work, using my heart to edit is also a very critical part of my process. I also usually ask my Indigenous women friends to do the same thing when they read my work, and this has proven to be the most lovely of processes.

Tell us about yourself.

I am a writer, story-teller, educator and activist of Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg ancestry and I live in Nogojiwanong (Peterborough, Ontario).

When did you realize you had a passion for writing?

Recently. I’ve written since I was a kid, but I don’t think anyone ever saw that in me and I didn’t see it in myself either.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

Lee Maracle was the first Indigenous woman writer I ever read and her work still breaks my mind and my heart. Thomas King has also had a tremendous impact on me and many Indigenous writers of my generation. I love the work of Anishinaabe performance artist Rebecca Belmore, and dancers/choreographers Santee Smith and Rulan Tangen. They often embody in their work what I’m (trying) to write about. Anishinaabeg Elders Doug Williams and Edna Manitowabi are fantastic storytellers and have both been tremendous mentors and friends to me. The paintings of Robert Houle. Ellen Gabriel is just an incredible orator, and this is where our stories really live. I’ve also been recently blown away by a new generation of Indigenous playwrights—Waawaate Fobister, Cliff Cardinal and Renellta Arluk for instance. Ryan McMahon, an Anishinaabe comedian challenged me to go to some more difficult places in my work. The academic work of Dene scholar Glen Coulthard, Mohawk scholar Taiaiake Alfred and Andrea Smith has also really challenged and changed my thinking. Junot Diaz, Richard Van Camp and Denis Johnson all taught me about the short story. The poetry/lyrics of John K. Samson, Tara Williamson, Boots Riley, bell hooks, Shane Rhodes, and Jon Paul Fiorentino. And of course Zoe Whittall, and so many others.

How and when do you find time to write?

I don’t know. Left to my own devices, no matter what situation I find myself in, I always seem to find time to write, often to the detriment of a lot of other things.

What has been some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced as a writer?

It is a very difficult challenge for Indigenous writers and writers of colour to access our audience, particularly those of us that write for our own communities first. My audience doesn’t read Canadian literary magazines, attend writers festivals or go to fancy book launches. So one of the things Indigenous writers have to do, is to build our audience by taking our work to where our community is . . . this often means self publishing, blogging and launching our work at community events. This is actually really wonderful because in my experience, there is no greater feeling than writing something and having the people that mean the most to you in the world connect with it. I was extremely lucky to find Arbeiter Ring Publishing—a publisher dedicated to publishing work from the margins—without them, I’m not sure I would be a writer. And of course, this is starting to change with all these great new Indigenous publications like Kimiwan, Muskrat Magazine and As Us Literary Journal, and that’s a very amazing thing.

How have you changed as a writer over the years?

As I get older, I care a lot less what other people think and I am far more willing to be vulnerable, take risks and speak my truth. That is one of the truly fantastic gifts of age.

Notifications