Walking through Glass

Joanne Vannicola

January 6, 2014

2010

I never knew what condition my mother would be in when I arrived at the hospital, if she would be lucid, sleeping, in an altered state, or maybe even gone, dead.

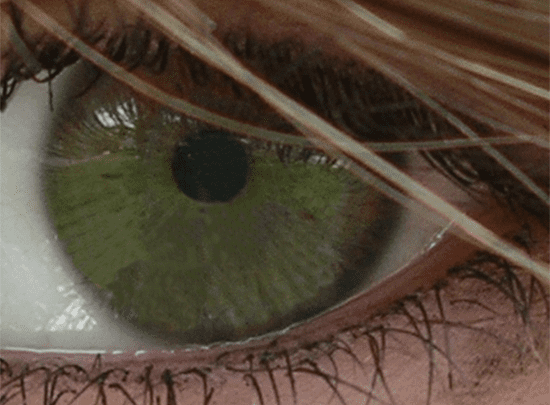

While snow melted and everything was slowly coming to life, my mother lay dying. I finished my cigarette outside, squatted on the ground in the grass. I cried and smoked and touched the grass all at once as if it were the fur of a sleeping cat. There were permanent dark circles set under my green eyes. My fingertips were yellow with nicotine where I chewed the skin from nervousness. Even the sky seemed scattered and uncertain as if the Spring sun might disappear and a storm might crash in.

“Are you okay? ” asked a woman who approached me in a gray suit, everything perfect and in place, stockings, heels, and a pearly face with red bold lips. I squinted, shielded my eyes from the light like a vampire as I looked up.

“My mother is dying,” I said with the sound of apology in my voice, still touching the earth with my other hand. I had forgotten that people could see me, and this stranger standing above me reminded me of human connection. I needed to tell someone in that moment and the woman in the gray suit would do.

“I’m sorry,” she said softly and walked away.

I stood up from my patch of soil, put my cigarette out with my shoe, crossed the street, went through the revolving doors and back up to my mother’s room. On the way up in the elevator I put a piece of peppermint gum into my mouth, fished my shades out of my pocket and put them on. It took forever to get to the seventeenth floor, an elevator crammed with patients in gowns and bandages holding their IV poles, or visiting guests and doctors. We all knew someone with cancer in this hospital. Some of us were here for those in the beginning stages of the disease with family members or friends newly diagnosed, in treatment or having surgery. Then there were people like me, the disheveled and overtired, the ones who looked like we hadn’t left the hospital in days, on constant duty, not wanting to miss the end, scared to go to the bathroom or steal away for a smoke, just in case.

The palliative care ward was quiet. My sisters were outside our mother’s room talking in whispers. They traveled from Montreal and Vancouver to say their goodbyes to our mother who had slipped in and out of consciousness over the last three days, almost in a coma, her eyes glassy, hollow, her body bruised from multiple needle entries from IV fluids, morphine, saline.

The rooms of the dying were small and sterile with no color, just bodies, wires, oxygen masks, gray speckles in the floor. I entered and sat beside my mother’s bed, where I had covered the walls with images of the natural planet, perhaps it was to remind me of my own life and to give my mother something beautiful to look at in her own quiet moments alone. Maybe it would calm her or maybe she could imagine herself in the images themselves, in Africa with animals, or by the edge of a cliff, or winged, able to see from a bird’s eye view.

Sometimes mother and I would stare into each other’s eyes as if we were thinking or feeling the same things, looking for a way to speak to each other, the pauses filled with a lifetime of stories desperate to come out, but now, nothing. She had been in a coma all night and morning. Her eyes were almost transparent, her mind far. I wanted to shake her, to scream at her even, but I knew she was dying and I just wanted it to end, couldn’t bear to see her vulnerable, in fact I hated it, hated looking into those glassy eyes.

My mother’s eyes in earlier times were full of expression, always on the go, rushing to get to lessons, dropping dad off at work, or the looks she gave us girls when she was mad. One look from my mother could silence me. In those days mother had long curly hair, round beautiful green eyes and a sharp tongue. When she was mad, all she had to do was look at you and you would know to shut it, and sometimes she might eke out a tiny phrase like, “If you even dare,” or one word, eyes like darts: “Don’t.”

But now, now her eyes were dull, heavily lidded from the months of morphine, chemotherapy and radiation treatment, now she was bald and her power nearly gone.