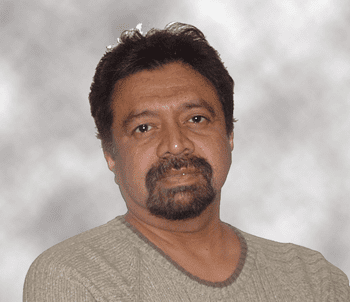

Even before Pratap Reddy migrated to Canada, he had dreams of becoming a writer. He had considered writing a comic novel about office life in India, but the only writing he did were a few newspaper articles (which were neither comical nor fictional). His real creative stimulus arrived in 2002, when the experience of transplantation to Canada became akin to getting a fresh set of eyes for Pratap. In reaction to completely new surroundings, experiences and challenges, he took up the pen and finally had a real go at creative fiction.

The coming-into-being of Pratap’s collection Weather Permitting can in itself qualify as a story of an immigrant trying to find his footing in Canada—an overarching theme in his work. The challenge of the new prompted Pratap to join writing groups, and later enroll in the Humber School for Writers. He began sending out his stories to magazines. Responses came in the form of rejections until Diaspora Dialogues picked up one of the stories in the collection—“Birthday Blues”—for TOK: Writing the New City, Book 4. A Mississauga Arts Council prize and a grant from Ontario Arts Council soon followed. Despite these initial triumphs, Pratap feels that the DD long-form mentorship program provided the crucial missing link: connecting writer to publisher.

A positive attitude and cultural familiarity with mentor-mentee relationships are the two things to which Pratap attributes the rewarding outcome of his work with mentor Cynthia Holz. Although his creative fiction is informed by the South Asian immigrant experience, Pratap wants as wide a readership as possible across cultures, so Cynthia’s eyes were a good gauge for that. As well, Cynthia’s big picture sensibility and sense of stories as traditionally narrated—rich in description and detail—was a perfect fit for Pratap. She allowed the stories to breathe, let them take up their space rather than constricting them into a style of overly economical writing that often acts as a puzzle for the reader to follow.

They developed a working pattern of Pratap sending Cynthia a couple of stories, receiving her feedback and, while rewriting those, sending her the next couple of stories to edit. One of the features of the long-form mentorship program is that mentors commit to reading no more than a pre-specified amount of words, Pratap kept in mind that a second reading of the same story would count towards the total. He and Cynthia concentrated on finessing his older stories from 2003/2004. His more recent stories, written after his training in creative fiction writing, were already in pretty good shape and not in need of as much attention.

Pratap likens the mentorship to the Indian tradition of the guru-shishya relationship, where the pupil seeks wisdom from the guru, the teacher. Having this common reference point made it easy for him to accept feedback from Cynthia. Certainly, one does not have to take a guru’s interpretation as final, he says, but thinking that one already knows how to do something perfectly does not preclude the possibility that one has been doing it perfectly wrong all along. Therefore, as much as writing is a subjective exercise, Pratap strongly advises to keep an open mind when receiving suggestions from mentors. Not only do mentors come with a lot of experience, but their reaction will be similar to that of publishers and future readers. Writing is a personal and solitary vocation; a mentor can point out what works and what doesn’t, and make suggestions to enhance the readability of a story.

At the end of his mentorship period, Pratap put rewrites of Weather Permittingon hold until he had received further feedback from DD’s own reader, DD president Helen Walsh, and the editor of Guernica Editions. Prior to submittingWeather Permitting to the DD mentorship program, Pratap had been sending it to publishers every three or four months, including—at a friend’s suggestion—to Guernica Editions. When Weather Permitting was accepted to the DD mentorship program, Pratap informed Guernica, and also told them that he would send them the edited manuscript when he finished the program. True to his premonition, the post-mentorship manuscript of Weather Permitting was picked up by Guernica Editions. Pratap has since signed a publishing contract with a projected publication date of 2016.

Next, Pratap plans to complete a novel, once again about the marginal life of a new immigrant, which is already in progress at 50K words. He also intends to write fiction set in New India, with all its glitz and glamour blinding one’s view of the dire circumstances millions live in. Pratap is often encouraged to expand some of his stories from Weather Permitting into a novel, but he is more interested in trying out new ideas rather than retreading the same ground.

As a writer whose work at times turns an unflattering eye on his community, Pratap understands that he might ruffle some feathers but he strongly believes that the background against which the stories are set must ring true. He maintains that the characters, however, are his own creation. A writer need not be a pamphleteer, forever in praise of his children themes, he says. Neither does one story represent all Indians. In fact, Pratap does not see new immigrants as the target audience for his stories. Rather, he thinks of the ideal readers as those who are interested in learning about others, who want to venture out of their circumscribed life and enter into unfamiliar worlds. He also believes that Indians in India will benefit from knowing what is happening in the lives of their fellows abroad.

The titular story of Weather Permitting deals with going home of a different kind. Regardless of origin country, most immigrants share the risk of losing face if they return home permanently, the implication being that they failed to “make it” in the adopted country. It is a decision that is never taken lightly, one that most will avoid unless on pain of death no matter how deep the disappointment of the new life. Similar to the main character Ravi, Pratap had to deal with many unsavory landlords, though fortunately never to the point of making him want to turn back. Another story, “For a Place in the Sun,” deals with the polar opposite: those who never go back. One sad occurrence amongst migrant families is that a husband, once arrived in the West, effectively abandons his wife. He severs all contact, often replacing her with a white woman. Such casualties are so common that when Pratap, in his early days as an immigrant, misplaced his cell phone and was out of communication with his family for almost a week, his wife joked that she had feared abandonment. Happily, that miscommunication was cleared up and Pratap’s son and wife joined him in Canada a year later.

Pratap’s penchant for the unexpected, twist endings may come from his early love of British detective novels. If you are what you eat, says Pratap, then maybe you are what you read as well. However, even that is a concession, his true preference being for open-ended conclusions.

In the world of diaspora literature, the work he admires most is The Nowhere Man by Kamala Markandaya. Written in the 70s, it resonates even today when immigration has become commonplace and there’s the comfort of having thousands of compatriots around you. For a window into contemporary South Asian diaspora life, Pratap recommends The Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri and The Storywallah, an anthology edited by Shyam Selvadurai.

Until Weather Permitting hits the bookstores, that is.