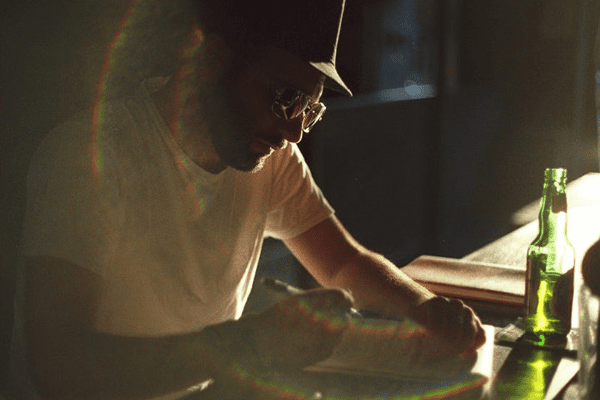

I always find that writing found poetry stirs up my creative side. Try collecting all the newspapers in the house, old love letters, recipes, grocery lists, old science textbooks and cut out the interesting words and sentences. Then throw them on the floor, and start picking up the pieces. Write down the words and sentences in their random order, and start filling in the blanks. You’ll end up with a whole new original poem!