I see you lurking in the shadows you silent oppressor I hear you knocking on people’s doors unassuming polite personable you come like rain from gloomy skies your water healing the people vulnerable you promise sun when there is none dawn cracks and the storm passes bright skies convince us you are truth we celebrate your courage and follow in your trail our blood drenching your muddy paths our hands heavy with your ideals we have become your following you silent oppressor

Shorthand

Mermaid Diaries

I’m running again. Running down the monotonously tree-lined Kingsway Crescent, the neatly alternating houses and driveways. I’m running and I hate it. There’s only a couple weeks left of school. I was hoping to be a stunning creature by now! Tonight as I run, my feet are pounding down the street to the lopsided rhythm of my breath—two in, two out. I still feel too humiliated by my jiggling, overtly touchy-feely thighs to pay attention to much else besides the squishing of my legs. This running is definitely not helping, I’ve decided. Each day that I run, I’m more aware of them. I grunt as I sigh out of my mouth and push myself to run down the street. I pass from the street down into the gravel lined road, it’s a steep pebbly decline down to the river road. Seems appropriate punishment for any unlucky exercisers like me. I let the hill carry my throttling forward down to the river with my knees jarring rough into each step. How is it that I force myself to suffer under the June sun to run for increasingly straining lengths, but it only seems to broaden my fluid legs even more. It only makes them stronger!

I used to love to go and hang around that Humber River path—to climb things and rollerblade. I just resent it now. The sun sets as I run down Kingsway Crescent to reach the sloping turn that leads down to the river. I run in the dim with leggings firmly encasing my legs, but loose enough to not be entirely irritating. It feels like I could convince myself there’s progress happening. The sky becomes dusky enough that I can’t tell the difference between it and the deep shades of summer clouds, the light warm pattering rain starts to fall a bit. Just softly meeting me, and gliding down my bare arms and soaking gently into my leggings. The rain warming on me and my sweat cools—mingling and it feels like joy. No, I’m wrong. I don’t hate running more than math class, than stiffening in my vinyl seat in a schoolroom, than the Loblaws checkout, than the loneliness of news anchormen echoing from the other room at home. But I can’t run forever, be in motion forever, I have to slow and stop after the river loop finishes and my legs walk in steps that shake them loosely.

___________

Tonight, after school and after work, I bike across Dundas and then Dupont, and get home for a run just as the sun was setting. I work at Loblaws sometimes, tonight is the first time in a couple of days. A sweltering heat wave has hit Toronto, it’s like a desert town now. Tumbleweeds blowing across roads, people sitting on cement steps sweating thickly—the unlucky air conditioning have-nots. It feels like I have forgotten how to be conscious when I fall into a stupor, laying on my stomach and watching TV or any moment I’m not dragging myself through school or sleeping. Today at work consists of an endless stretch of staring blankly out of my cashier station at the floor-to-ceiling front windows, with the pale reflection of grocery lanes superimposed on the street outside against the glass I am looking through.

I tried running on the first of those hot, hot days and the air was so thick, hot, difficult to push through. Dust, and smog, and hot, and sun weighing down on my body, I swear, it felt like the dense air was breathing more life into my blooming legs, as I forced my way through it. There weren’t any of the usual families, runners, or bikers around. I finally let myself walk the rest of the way and slouched home, defeated, I tried not to feel my legs too keenly.

Those girls at work with me, they seem so vibrant, the way they move themselves—who they are is stretched out to the full breadth of their body, they have life in every part of them. They comfortably and confidently move through the world with that vitality I envision suddenly arising when my legs are slim enough. And if not that, if they are more fully hipped than slim and lean, they fill up and absorb all the space given—when my own body gains ground against my diminishing self, as the soul of me withdraws in defeat, and becomes more compact.

There at Loblaws today, I watch the lane two girl sidle out of her position to join her friend at the cart as they casually push it away together. I stay stocked still and stare at the backs of their legs, I couldn’t help it. They bop along with animated conversation between them, the skinny one’s pony tail waving in the wind to the rhythm of her walk. Neither of them wear the strict Loblaws-issued attire, but they’ll never be called on it by Loretta, our alternating doting and severe Front End Supervisor. The girl on the left, her thighs don’t travel down lean and clear of one another like her friend’s. But she’s beautiful. Her legs are a seamless black contour swelling out from her hips in sloping curves. There are stretches of horizontal pulls of fabric running from side to side across the pants at the back of her legs, where her thighs subtly stretch them. I watched each firm step that pulls one plush leg against the other in a brush against themselves, forward in a fully feminine friction that keeps me entranced in my envy until she has moved too far away.

Now at home, I feel exhausted from sliding from checkout screen to plastic bags constantly, repetitively. I lie in bed with the familiar lethargy of this heat wave. My thighs still feel squishy but all my skin is so prickly and dry. As if the pores in the lower half of my body have been breathing in the brittle dust of the hot air, pulling in the dryness. Maybe, hopefully, it’ll draw that deep inside and dry up and shrivel out my full thighs into smallness.

But my only feeling of shrinking is something like my spirit pulling in, like the me that exists is not large enough to stretch to fill in every crevice of my body. At home in my room with its dark hardwood floor that creaks comfortingly beneath my feet as I move within its four walls. I take off my uniform. The green Loblaws shirt is baggy and stiff—it both enshrouds my body and restricts it. My body looks the same staring down at it here, between the two pale green collars and button seams, as it did inside the cold beige bathroom stall in the work change room. I was certain that I would be able to move freely and exuberantly if I didn’t have to worry about whether I’d jar anything loose. If I could let my petite personality loose into all of my body, but this body looms away so beyond control. It doesn’t adhere to rules of justice—it’s this strange thing, all its own, that’s swallowing the rest of me up. It’s a violation of me, this renegade body.

___________

Aahhh! I don’t know, I don’t know what’s going on! It’s only the morning after I wrote all that, but things have changed drastically. I’m heading towards school on the TTC. I should be panicking, but maybe it’s the lingering lethargy from the heat that has now broken, or maybe with only a couple of days left in school all I have to be concerned about for now is just to make it out of the house discreetly. If I’m just at home, perhaps a summer vacation of laying down and taking in the television will go almost unnoticeable. Alright—what happened.

When I woke up this morning, I couldn’t separate my legs above the knees. Getting out of bed was weird, but it was early . . . Sometimes my eyelashes stick together, or I can’t see when I get up quickly and all the blood rushes to my head, I assumed it would regulate in a minute. When I awkwardly slid out from under the sheets, I stared down. Sometimes in hot summer nights I wake up not wearing clothes. I suppose that happened, my shorts and underwear were crumpled up at the foot of my bed. My legs—from the knees my legs could move and step and turn as good as ever—but above the knees, all the way up, they were stuck together.

My seat on the bus is draped over with a blue silk flowing skirt I happened to have, the backs of my knuckles rest just under my legs, where the skirt edges the seat. I brush my fingers against the fuzzy red fabric of the seats and stare out of my dirt-spattered window at the familiar scenery of my bus-ride to school. Plaza parking lots and the dry cleaners. Grass medians before the Royal York exit and the small gated cemetery on the right side, next to a little community of mid-sized houses that can be peered at just over the tree tops.

This is baffling, but there aren’t even any lines down the middle of my merged thighs. They’ve fused! And so evenly. Just one wide and looming thigh—joint to the knob of my knees, where they emerge out as separate legs. I seem to be taking it remarkably in stride somehow. I manage to find this ankle-length skirt to wear. It’s long enough and flowing enough—blue draping silk—to mask my melted thighs. From beneath the hem of this skirt I can only see the clean angular boniness of my ankles, and my legs are still clear and clean of each other from knee to heel. I hope the point of fusion that’s been brought down through my thighs to my two knees, like a zipper being zipped down from my hips, has descended as far as it will go. And despite walking slowly I might be able to pull off walking with a range of motion only below these locked knees . . .

___________

After a long languid walk from school, I didn’t get home until the rest of my family had already finished eating dinner. I made myself a plate of leftovers while a television or radio buzzed dully in the other room to a few assembled, and there were footsteps creaking upstairs.

I wonder, will the merged thighs extend past my knee? I don’t think it’s at my calves, but I swear they’ve gathered around. I should contemplate my next move after school goes by—it’s been an endless stretch of waiting for the day to be over so the next one can be over too. Day in and day out, a few days ago I thought would just begin the same again next year.

Our neighbours have apparently offered to have my family stay at their old cottage for the weekend, starting tomorrow. On Georgian Bay, and I’m told the house is right on the beach off the shore of that choppy lake.

I never understood the point of baths. Just sitting in water, waiting. But here I am in one now. I want to see how it would affect these hard scaly things popping up all over my uni-thigh. As I splay my fingers above my knees, deeply contemplating and considering this remolding body, the darkening patches of rigid but shiny smooth skin that has grown. I feel easy, relaxed in the water, but I shouldn’t be, with these rough patches spreading. Is this whole shifting thing spreading farther down? How far? Under the water, the little scaly bits begin to tip upwards at an angle—tiny bubbles float up out of the cracks. It’s dark underneath these things on my skin, and I don’t want to look.

I’ve been staring out at the lines of trees, dappled yellow fields, and old fences whipping past, and finally out the car window I see us draw close to the cottage on Georgian Bay. There’s an overwhelming sense of finality here . . . I’d be willing to say that the condition of my legs has exaggerated even more, but I don’t mind enough to check and pry at it. Once all the cottagers have assembled, car doors are slammed and gravel is crunching underfoot, they then swan inside to begin having wine while cooking dinner, unpacking, and digging up games. I go around the side, taking my time, to gradually reach the beach. All I want to do or can think of is getting to the water. I don’t pay much attention to threading my toes through the dunes as I always used to, even if I can barely move my steps forward at all—my legs join now at the outward curve of my calves. A little elastic and malleable still, but closing in.

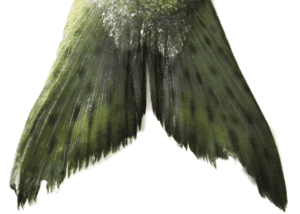

I’m finally at the water. I don’t know why, but I absolutely know writing these words is important. My steps to bring my toes into the lapping shore seem tremendous. The narrow range of motion at the knees makes me lift each toe timidly toward the waves. As soon as I touch my toes to the water, I feel an overwhelming physical surge in the lower half of my body—needing to feel that wet all over everywhere. I push myself forward until the conjoined leg meets the water—the little scales grow beneath the point where my legs are merged, and the scales of those inner sides of limbs still separate and start to partially break off. Only half-attached to my leg still, the scales wave sideways in the water, but clinging on. I know what this means. I shuffle my ankles together and the waving stretching scales enfold in one another along the separate calves and ankles, to my feet and toes. They’re drawing the last bits of my legs together. I teeter slightly, my centre of balance narrowing to one beam—I look over at the cottage for one vague moment. I look at this diary, I don’t know whether to bring it to the waves with me or throw it to the beach. I don’t know if it will matter either way if it falls through the water. Whether it’s retrievable or not. I hold this book in one hand as I take off my skirt, shirt and bra. I skitter out farther into the waves, I can still see the form of my feet, but they’ll be melting away soon too. Smoothly I slip sideways off my balancing feet. Covered in scales, in the water my feet mold together and then branch out into something slim, flat, and strong. And this is what they are—mermaid thighs. I’ve changed fully, and now I’m going to join the waves and the water. I’m holding my diary and pen as I float above, close to the shore for the last time, knowing I’ll let them go soon.

My Double Life

“Oh Simrathy,” my grandfather says in his deep, gentle voice. “How is school? ”

I look up even though that isn’t my name. But years of answering to it have made it automatic.

“Good. Busy,” I answer mechanically. “Since it’s my last semester, I have to finish my final assignments and exams before I do my teaching placement.”

This answer satisfies him. Not only have I mentioned studying and working hard, but the reminder that I will soon follow in his footsteps as a teacher fills him with pride, and he smiles. There are few professions that satisfy my Sikh grandparents, and teaching happens to be one of them.

I glance across the room at my sister Natalie who is sitting next to my grandmother, scrolling through her Blackberry and trying to avoid scrutiny. She looks up at my answer and rolls her eyes, knowing their scorn for her marketing courses. Unless it’s law, medicine or education, it does not cut it in their eyes. I smirk and return to my cell phone as my grandparents launch into a lecture in Punjabi directed at my father. It’s funny to us that our father can sit by and listen to his parents reprimand us for our life choices, when he himself has made so many they disapprove of. My grandmother argues in her usual angry and hostile voice before changing her attention back to me, with it switching back to English.

“Simrathy, you are almost done school now, when will you learn cooking? ”

“I know how to cook.”

“Oh really, you know aloo gobi? Or saag? What about daal? You can’t even make a round roti.”

“Yeah, you always said when she rolled them, they look like Africa,” Natalie jokes. Across the room my other sister Jordan laughs, but says nothing.

I am reaching the end of my university education, a time that coincides with my grandparents beginning to think about arranging a marriage for me. Beneath this larger aim they are beginning to fret about my inability to cook their traditional food, which is a failure that will cause me to be undesirable to my mate, whom I will be expected to serve.

Only I don’t plan on serving any man the foods my grandmother worries I will never be able to cook—sabji, curry and roti. Yet I still can’t stand the manipulative way she is trying to imply my impending marriage and she can’t even bring herself to say the word husband.

My phone vibrates in my hand. Incoming text. It reminds me of what my grandparents don’t yet know: I may already know the man I will marry. His name is Kevin. And he isn’t a Sikh.

I look around the room, filled with the African violets that my grandmother has so tenderly cultivated, and a massive painting of their religious deity—Guru Nanak Dev—over the fireplace.

I sneak a glance at my phone: “Want to grab a beer? ” Kevin has texted.

I open my mouth to challenge her comments but my grandfather cuts me off. “What your Dadiji is trying to say Simrathy,” he says calmly, drawing out the final vowel sound in my name like he’s done since I was little. “Is that cooking is a valuable skill and you girls should learn. She can teach you.” I know he is just trying to keep the peace but I can’t help but resent his comments.

“Your mother wouldn’t let me teach her either,” my grandmother says, adding, “and see what happened with her.”

I glance over at my father, who is staying out of this argument, as he always does. Yet I’m suddenly enraged that he hasn’t done more to stop it—not just today while we sit in their living room, but in general. He should have ensured that their unreasonable expectations were not placed upon us, like they were on him. Maybe it’s just been his way of keeping the peace, as my grandfather always tries to do. But I simply smile at my grandmother.

“Actually, I have always wondered how to make your samosas,” I say. Meanwhile I respond to Kevin’s text, “I’m in, see you at 7.”

Just another day in my double life.

___________

I never thought I would marry an Indian man. No matter what traditional expectations my deeply religious Sikh grandparents placed upon me, I never doubted this fact—probably because I have always led a double life, having grown up in a community where doing so was perfectly normal.

I was born in 1987 into what can only be described as a mixed and subsequently turbulent family. My mother is mixed herself, born in India to a Goan mother and Portuguese father. My father was born in Uganda to Sikh parents. Both being Indian, one might assume that their relationship was blessed by both families, but this wasn’t the case. My mother was not chosen by my grandparents and furthermore she was not a Sikh who attended their temple.

My mother is the eldest of two girls, while my father is the middle child, with one older and one younger sister. As the only boy in his family he bore the sole responsibility of carrying on the family name. This led to disastrous consequences as he rejected the faith of his deeply religious parents, and in doing so abandoned any semblance of cultural tradition. This meant that he ignored his parents’ strongest wishes and refused to have his marriage arranged. Instead he married for love—a choice that would cause a divide in the family, one that would never be fully repaired.

Though my parents led quite different childhoods, their families shared a common thread—their parents, like all immigrants, came to Canada and struggled to give their children a chance at a better life. Upon completing high school, both of my parents chose to go directly to work instead of pursuing a university education. They both landed jobs working for the Government of Ontario; when they met, my father worked his way up from a lowly start in the mail room while my mother was a co-op student in the finance department.

My paternal grandparents were less than thrilled about my mother. They had high hopes for their only son and were not impressed that he had selected his mate in such a rebellious fashion. When my parents wed, there were numerous familial hurdles to clear. The wedding posed a particular problem. My mother, having been raised Catholic, wanted a traditional church wedding. My grandparents insisted on a traditional Sikh wedding for their son. The compromise was to have two weddings—one of a calibre my mother had always dreamed, and another to satisfy the religious and cultural expectations of my grandparents.

So began my troubled double life.

When I was born about a year after my parents’ wedding, there was turmoil in the family. My father disregarded tradition by cutting his hair for the first time since his birth and removed his turban. “I don’t want my children to grow up in a world where they know me as a man with a turban,” he told my mother. The iron bracelet called kara—a symbol of his induction into the Sikh faith as a child—that he wore on his wrist was the only visible symbol of the Sikhism he retained. (Years later I would ask him why he kept the kara when he had removed himself from every other aspect of his parents’ religion. “I can’t get it off my wrist,” he told me simply.)

My parents insisted on naming me themselves, something that upset my already enraged grandparents. According to Sikh culture when a child is born, the Sikh holy book—called the Guru Granth Sahib—is opened to a random page and the first letter of the first word at the top of the left page is used to create the child’s name. My parents had refused to partake in the ceremony while my grandparents, refusing to give up tradition, ignored my parent’s wishes and chose a name for me in this traditional manner. It is for this reason that my grandparents do not refer to me by my legal name, Celia, and instead refer to me by the name they chose, Simrath. In years to come, the same events would unfold surrounding the naming of my two sisters; they too are referred to by their Sikh names, Natalie is Sandeep and Jordan is Nimrath or Nemu for short.

Today, when I explain my family situation to other people their advice is always the same: rebel. That the scorn of and disapproval from my grandparents would eventually subside and lead to acceptance. But what these people don’t understand is the stubbornness of my grandparents or their ability to hold a grudge. Never has this been exhibited more clearly than in my first year of life. My grandparents were so hurt that my father had not only rejected their faith but had also refused to let them name his child—a girl who would obviously not carry on the family name—that they refused to see or speak to my parents at all during my infancy. They lived mere blocks from our home in Markham, but the distance between us was enormous.

My parents eventually worked things out with my grandparents over the name issue but our lives were still fraught with constant clashes between the cultures. There were arguments over the way we spent money or the fact that we ate meat. Their frugality (more of a cultural than a religious characteristic) led them to believe that the weekly pizza our parents ordered while we watched TGIF was an obscene waste of money. The fact that we ate meat—which is forbidden religiously –infuriated my hot-headed grandmother. She took my picky eating habits as a sign that her strictly vegetarian fare was not good enough for me. She would frequently scoff at me during meals exclaiming outrageous statements such as, “You don’t want to eat my roti but you will go home and eat Kentucky Fried Chicken, fine!” Over the years, I followed my parents’ cues and developed a thick skin for her denigrating remarks, letting them slide off my back instead of allowing them to provoke me.

My grandparents also hated the fact that as a result of my mother’s Catholic upbringing we celebrated Easter, Thanksgiving and, to their horror, Christmas. I remember one year over Christmas vacation my grandmother asked why we didn’t come to see her on Christmas day. “You don’t celebrate Christmas,” I offered, puzzled. “Uh huh,” she nodded, “I see.” I never understood her problem with us celebrating both holidays, but later realized that it must have been her way of accusing us of favouring Catholic tradition over her own.

As we got older they began disapproving the way we dressed. Summer attire was particularly problematic around their house as my grandmother could not understand why we wore shorts and tank tops as opposed to the cotton Punjabi suits that she wore. “Why are your shorts so small? ” She asked Jordan once, “Are your legs hot? ” Over the years we learned that it was easier to hide these controversial details from them than to argue. Concealing things became one of the tasks of our everyday lives. My father would insist that we hide liquor bottles when my grandparents came over, as if he was an under-aged teenager, since Sikhism strictly prohibits alcohol. He also began to insist that we change our clothes before we went to visit if our shirts were something that might be considered too low cut, too tight or plain inappropriate by my ultra-conservative elders. We did these things to appease them, not upset them, and to make our lives easier.

The façade we had constructed seemed quite normal to me throughout my childhood. I grew up in a neighbourhood in Markham where most of my friends were first generation Canadians, if not immigrants themselves. We were all accustomed to hiding the “Canadianized” aspects of our lives from our more traditional relatives. Most of my family (as did I) attended religious ceremonies at their various places of worship with their pious relatives and not understanding a word that was spoken, since unlike their parents, their first language was English. Many of my friends could not speak to their elders for lack of comprehension of their mother tongue. I was all too familiar with this reality; although my grandparents spoke fluent English they preferred to speak Punjabi and frequently my mother, sisters and I would find ourselves staring blankly into space as a raucous group of my father’s relatives chattered incomprehensively around us. Not being able to speak Punjabi was normal to me, the same way concealing Westernized aspects of my life from relatives was.

When I was 13-years-old my family moved to Whitby and there my double life exploded. Unlike my peers in Markham, the kids in Whitby were quite often 5th and 6th generation Canadians. A shocking number of kids had ancestors who had always lived in the Durham Region. This was a stark contrast to the diversity I had experienced growing up. In Markham I had been surrounded by people living lives exactly like mine; in Whitby I considered myself to be a freak. Though I am fair-skinned due to my mixed heritage, I didn’t exactly blend in to the predominantly white population in Whitby. My peers in high school were mainly blonde-haired and blue-eyed so it is not an exaggeration to say that I stuck out. I quickly developed an inferiority complex that would last through to university.

My status as the “new girl” was exacerbated by my confusing heritage. I recall a time where I thought I had made a friend in one of my 9th grade classes. I was getting to know the guy who sat next to me, when he bluntly asked: “So, are you, like, black? ” The shock of his ignorantly racist question turned my stomach. I realized that I was coming of age in a community with so little diversity that the distinctions between cultures were actually as simple as black and white. Here the problems were so much different than mine had been previously. In Whitby, kids didn’t hide things from their families and worry about if their friends would see them wearing Indian clothes to the temple on the weekend; here, they worried about how they would finish their homework between hockey practice, soccer practice and school and whether they would spend Christmas with mom or dad this year. In Markham, I didn’t know anyone whose parents were divorced and after school was spent doing extra practice in “maths” as our Asian families would insist if our homework was done, certainly not playing sports. I longed to fit in with these Whitby kids but I spent most of my high school career believing that I was an outsider looking in.

Emerging Author of the Month: Sarena Parmar

Tell us about yourself.

I grew up in Kelowna, BC. I had taken a creative writing class in high school, but never thought much of it. I went on to pursue my career as an actor. I studied collective creation with One Yellow Rabbit in Calgary and commedia dell’arte in Italy. But my main learning happened at the National Theatre School, where I studied acting for three years. In my second year, we had to create a ten-minute solo-show. And I immediately thought, oh shit! I have nothing to write about—nothing I wanted to say. But eventually, I created a piece called Inheritance. And after that I realized maybe I do have something to say.

My trajectory as a playwright has been a shy, slow growing emergence. Always apologizing for being an actor first and a playwright second. But slowly people showed interest in my work, which allowed me to build skills and confidence. Inheritance was accepted into the Diaspora Dialogues mentorship program, and grew into a one-act, three woman play. I created a one-woman show, Through the Lens, which was invited to be a part of the Summerworks Youth Reading Series. But it has only been in the last two years that I have begun to identify myself as an actor AND playwright. I was part of the Cahoot’s Playwriting Unit last year, which was a huge turning point for me mentally. Currently, I am working on a re-imagining of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, based on my personal experience of growing up as an orchardist. Set in the Okanagan during the Trudeau Era, it follows a Punjabi-Sikh family fighting to save their orchard from foreclosure. The play examines the minority experience in rural Canada and the search for a better life, at a time when multiculturalism was born and anything was possible.

Tell us about the piece you’ve decided to share.

This is the first few pages of a piece called The Park. The play began as a short writing exercise, but I quickly realized, there was something bigger I wanted to explore with these characters.

The play examines what happens when two unlikely strangers meet. Both characters want to connect so badly with another human being, they are blind to the consequences. The Park looks at the dangerous lengths people will go to in order to survive.

When and why did you realize you had a passion for writing?

When I realized there were stories I wanted to tell, needed to tell. And that no one else could tell them; because no one has had my experiences, history, or emotional makeup. I believe we all have that ability and uniqueness in us.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

I don’t know if any one writer has had THE major impact on me. Because I work in theatre and television as an actor, I am constantly surrounded by writers, scripts and stories. I think I took for granted what I’ve learned about playwriting or who I have been influenced by. But it is the everyday events that have the biggest impact on me. I see a moment happen in real life, and it rings true to something so much bigger. I ask myself: why does this move me? And how can I create this feeling in my plays?

What kind of writer do you aspire to be?

A writer that can show the ugliness and beauty of the human condition. We, as human beings, are so complex. It is endlessly fascinating to me.

How and when do you find time to write?

It is definitely hard to find time to write. I’m not the type of person who can schedule only an hour to work and actually get something on the page. It takes me a while to get settled and filter out distractions. So I’ve started creating self-imposed writing retreats. I’ll book off five days and do nothing but write, sleep and eat. It allows me to clear my mind and immerse myself in the play.

The Park

An empty well-kept park, late at night. It’s cold enough to see your breath.

Elizabeth is huddled underneath a tree.

Elizabeth:

Twinkle, twinkle little star. How I wonder what you are. Up above the world so high, like a diamond in the sky. Twinkle, twinkle little star, how I wonder what you are . . .

It’s friggin’ cold out here. I wish I had my other mitts. The blue ones. I’d look a lot tougher with the blue ones. Johnny wears blue mitts and he never gets beat up. Ever. I wish I was more like him. He never lets anything show. Not like me. Stupid girl. I cry too much. Laugh too loud. (Beat) Look at that . . . All the clouds are gone. The moon is just up there . . . for me only. I wonder if tears can freeze like raindrops. I wish I was up there with the stars. They don’t look lonely, they have each other. And stars are made of fire, so no one can touch them, hurt them. Leave me alone! Don’t touch me! Anybody! (Beat) The wind feels good. Cold. Icy cold on hot cheeks. I like it here in the dark, where no one can see me. Hear me. I look like a shadow. Except for these stupid mitts! Why! Why did I pick the brightest mitts in the house to wear? My stupid mom . . . she’s always trying to tart me up.

John, a handsome, well dressed man in his early 30s, enters.

John:

Hey there. You didn’t get wet in the rain. (Beat) I can tell because your mitts are dry. What’s your name?

Elizabeth says nothing.

John:

I’m John.

Elizabeth:

My brother’s name is John. Well, Johnny.

John:

It’s a good name.

John sees Elizabeth staring up at the stars. They look up at the sky together for a moment.

John:

You know why the sun and moon can never be in the same place? Because the sun is so hot, it would melt the moon. Because, you know, the moon is made of ice . . .

Elizabeth:

That’s not true. Are you stupid?

John laughs a little.

John:

Ahmm . . . You wanna smoke? I’m in love with these smokes! I have them specially imported from Argentina.

Elizabeth:

Oh. Does smoking make you a grown up?

John:

Yea. I suppose it does. Adults only.

Elizabeth:

I don’t ever want to be an adult. All they do is –

There is a loud rumble in the distance. It almost sounds like a man shouting.

Elizabeth:

(Rattled) I heard if you’re a grown up, nobody can hurt you.

John:

I don’t know if that’s true.

Elizabeth:

I want one. Gimmie, gimmie a cigarette! (Beat) My name’s Elizabeth.

John gives her a cigarette.

Elizabeth:

It’s freezing.

John:

What are you doing out here kid?

Elizabeth:

Teach me what to do with this thing. Ah come on, don’t be a prude. Hey Juan!

John:

What did you call me?

Elizabeth:

Come on, I’m just teasing. Argentina cigarettes . . . ?

John:

Ah, sure, right. Hold it up. No, in your mouth. Good. Now ummm . . . it’s windy so . . .

John cups Elizabeth’s hand to shield the cigarette.

John:

How old are you?

Elizabeth:

Practically fourteen.

John:

Look, you should probably be getting home to your parents.

Elizabeth:

Sick of me already?

John:

Pretty girls like you should not be out this late.

Elizabeth:

You think I’m pretty?

John:

Fuck, kid. Just go! Shoo.

Author of the Month: Ibi Kaslik

Tell us about yourself.

My name is Ibi Kaslik and I am a novelist and freelance writer. I am the author of Skinny and The Angel Riots. I am a creative writing instructor at U of T’s School of Continuing Studies.

When did you realize you had a passion for writing?

I think I always knew. My father is a writer so we grew up eating books for breakfast. I learned to read in kindergarten. It was like unlocking a secret door. Books are power, knowledge and escape; books were everything to me as a child: if I had a book, I was fine.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

Probably, as a younger poet and writer, clichéd as it sounds, Sylvia Plath. I was also very heavily influenced by music, namely David Bowie who created characters like Ziggy Stardust and structured albums around character-driven narratives. The photo I have enclosed reflects my “Heroes” Bowie phase. I admire Canadian writer Barbara Gowdy and American writers like Amy Hempel; Marilynne Robinson; Mona Simpson; Donna Tartt; Joy Williams and many of my colleagues at U of T, namely Alexandra Leggat and poet Catherine Graham.

How and when do you find time to write? / What has been some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced as a writer?

I’m going to group these questions together as my biggest challenge with teaching is finding the time to write. Once you get over the fear of the page, which happens every day, it is okay. You just need the time to think and dream and ponder; that too, is part of the writing process which daily life doesn’t often afford.

How have you changed as a writer over the years?

My writing has always been muscular, fierce and non-linear but, as I’ve grown older I have, hopefully, been able to control it more. The themes I explore are always the same: family, abandonment, betrayal, loss. I am also interested in what makes people self-destruct and make bad choices. I like setting challenges for myself by creating characters who are complex and not necessarily morally sound. I don’t like loveable people in fiction; I think it is more interesting to write about broken people.