He moves haphazardly, blown along the pavement in uneven gusts, like ricepaper. The oldest man in the world. Not for him, beneath that mask of grey enamelled hair, dried dreams of palaces floating on their pools of silken poetry or orchideous concubines in rites of silk. More likely a drab exchange of servitude Eastern soil for saltfish and the crudely offered tithes paid daily on the mackerel counters by us lazy blacks who’d rather spend than sell: the necessary sacrifice of language and the timeless shame of burial in this uncultured soil. Yet in the intricate embroidery of that face are all the possibilities of legend— Kublai Khan in rags. Loud-limbed and less ancient I defer the pavement to this parchment schooner with no port, this ivory chorale of semitones.

Shorthand

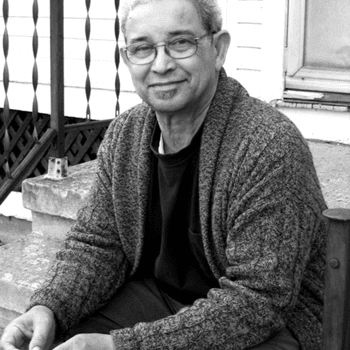

Author of the Month: Martin Mordecai

Tell us about yourself.

I’m a writer. That’s what I tell border guards—though to tell the truth, I feel a sort of brazen shiftiness as I make sure to look into their eyes and say it. I’ve only published two books, after all, one co-written with my wife Pamela, who has a much longer bibliography across poetry, prose, plays, and literature for children—a real writer.

I’ve told border guards different things over the years, all of them more ‘true’ at time of telling: civil servant, diplomat, journalist, television director, publisher, bookseller, even (when I’m carrying the paraphernalia) photographer.

But I guess ‘writer’ is true at this time: I don’t do anything else.

When did you realize you had a passion for writing?

When I ran out of other options for making money. More accurately, in 2000, when the Toronto Arts Council gave me a grant for a piece of writing I’d been playing around with for 20-or-so years. As a taxpayer myself, I felt (and still feel) an obligation to work hard to complete a project. That one became my first novel, Blue Mountain Trouble (2009). Other grants since then have transferred the sense of obligation to other projects.

I’ve always scribbled. At high school (in England—a very long story) I was blessed—as so many writers are—with two teachers who were passionate about literature, and knew a vast amount about the literatures of England and Europe. With their encouragement, I started scribbling then.

Returning to Jamaica at nineteen, I continued scribbling. A few poems and a story were published in the Caribbean, but I had no real ambition to be ‘a writer.’ Writers were god-like creatures in my life (and to some extent, still are). From childhood onwards I’ve been surrounded by books, wherever I’ve lived. I often say that home is where our books and music are—right now it’s Kitchener, but at different times it’s been Jamaica, Trinidad, Washington D.C., Boston, Toronto.

And wherever I’ve been, even in hotels and temporary lodgings, I’ve scribbled. I don’t know if that constitutes a passion for writing. But the passion for reading—the foundation of any writer, I firmly believe—and for music, remain.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

I’d have to begin with the King James Bible, whose language is the groundation of almost all Caribbean literature in English.

After that: Kamau Brathwaite and Derek Walcott, poets who, in their completely different ways, demonstrate the possibilities for using English—the KJ Bible again, but also the endlessly variegated languages that our histories have engendered—to create literature for and about the Caribbean, which is mainly what I do. (Exile, albeit voluntary and pleasurable, focuses the mind on former things and ways of being.)

For prose, I find Latin American literature inspiring, especially Gabriel García Márquez (who calls himself a Caribbean writer), Jorge Amado (who writes about a part of Brazil that is very Caribbean), and Eduardo Galeano, who writes alternative histories of the Atlantic world. They have been served by superb translators, but I sometimes say that it would be worth the effort to learn Spanish and Portuguese, even at my age, just to read them in their original languages.

But insofar as all reading influences a writer, I can also mention some non-hemispheric authors, from Somerset Maugham, H.E. Bates, and Graham Greene, to Truman Capote, Ursula Le Guin, and John Steinbeck (who, incidentally, began his working day by reading something from the King James Bible), Mark Twain (my desert island author), and Damon Runyon, a favourite of my father’s, who didn’t waste time with Grimm and Mother Goose when reading to his children.

How and when do you find time to write?

I try to do a few hours in the morning, as early as I can start. If that goes well, I’m set for the day: energetic, calm, cheerful—and, as my wife will tell you, I’m not naturally cheerful or energetic. That feeling sustains me through the period of the day when I have to do other things (driving, cooking, snoozing—a must at my age) and leads me to that point I remember Ernest Hemingway saying was his goal for the day: Knowing where you’re going to resume. In his case that meant the next morning; in mine it means the early evening of the same day, which may go on for a few hours. I know that 90% of writing is re-writing, but I don’t do as much of that as I should, until I absolutely have to.

Like right now. I’m re-writing a novel I’ve been working on (scribbling at for near forty years, writing seriously for perhaps ten, from the year of my first Canada Council grant) which is being transformed as I re-write. I tell younger writers who ask: ‘Follow the characters, and the language. Step by step.’ Some completely new thing will emerge.

What has been some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced as a writer?

Making a living. In that I’ve been immeasurably helped and immeasurably supported (emotionally, spiritually and, very importantly, financially) by my wife Pam. Without Pam’s royalties we’d be living in homeless shelters and tapping out our words on computers in public libraries.

The other challenge is confidence. I’m currently revising what sometimes seems to me my life’s work, a historical novel set in 1831-32 Jamaica, dealing with events that have been exhaustively written about by Caribbeans and other scholars and novelists (the former of whom I’ve read some, the latter of whom I’ve avoided like the plague—confidence again). In the novel, I’m coming at some things from an angle, so to speak, and there are moments (several each day) when I feel an abyss of darkness opening under my typing chair. But I press on—I am, I remind myself, a taxpayer funded by taxpayers. And—give thanks—by a wife who believes in what I’m trying to do. In that context the other challenges seem small.

How have you changed as a writer over the years?

I’d like to think I’ve gotten better—whatever that means—at saying what I want to say. In truth, I’d really like to think that I’ve learnt more about what I want to say! But who knows? I haven’t written enough.

The Elephant in the Mountain

The first time my sister and I were left alone to look after our eight-month old baby brother, he wouldn’t stop crying.

“Eric, what’s wrong? ” Ally put her hand in the crib and let him grasp her index finger.

Eric kept screaming, mouth open, eyes shut.

I picked Eric up out of the crib—his tiny hand still holding tight to Ally’s finger.

“Did you burp him already? ” Ally asked.

“Yah. He spit up a bit.” I pointed to the stain on my t-shirt near my collar-bone. A mix of baby food: peas and strawberry. When I’d fed him, I had to slip in a spoonful of the peas after every other spoon of strawberry, otherwise he’d spit the peas out right away. A look of disgust, one I wouldn’t have thought a baby could make, came each time he tasted the peas. The next spoon of strawberry made it better, and he held his mouth open again. I got him to finish both jars like Mom had said.

“You changed him already? ” I asked.

“Right before you fed him.” Ally quickly undid the diaper sticker and took a peek. “Nope. Eric, what’s wrong? ” She ran her fingers through his soft, black hair.

The cries kept coming. I carried him over to rocking chair by the window in our parents’ room. I rocked the chair back and forth, but Eric continued to cry.

Our parents had gone to the funeral home for their old driving instructor—she had taught them both to drive when they first came to Canada. Dad had found the driving instructor’s obituary in the newspaper; he paid attention to things like that. He always read the paper and knew what time the bank closed when Mom asked.

Mom had told us they would be back before long. She reminded us that the O’Brien’s were home next door, and the emergency numbers were on a piece of paper held on the fridge by a photo magnet of a real estate agent with a fake smile. Mom always worried about emergencies. She kept baking soda next to the stove and had so many flashlights in the house that Ally and I prayed for a blackout. “And don’t answer the door if it’s not someone you know,” Mom had said, just before she left. She used to say, “Just tell them, my mom’s in the shower,” not wanting us to tell a stranger we were home alone. But then one time a few years ago a man and a woman came to the door with a Bible. When the man asked if our mother was home, Ally said, “She’s in the shower.” The woman asked if our father was available, Ally hadn’t anticipated this question, and glanced over at me. I said, “He’s in the shower too.” The man and woman eyed each other, and said they’d come back. That was a few years ago.

“Should we call Mrs. O’Brien? ” Ally asked me over Eric’s screams.

“Mom and Dad won’t ever leave us home alone with him again.”

“Maybe he’s sick again,” Ally said, and felt Eric’s forehead.

Eric had caught a cold a few weeks back. I remember he had a mini-cough, and when his nose got stuffed up, Mom had to suck the liquid out from his nostrils and then spit it out. I thought it was the grossest thing I’d ever seen. “What else can you do? ” Mom said. “You can hold a tissue up to a baby’s nose, but telling a baby to blow isn’t going to work. I did the same for both of you when you were babies because I love you.” I loved my brother, but I wondered if I could ever do something like that.

“He looks okay,” I said, feeling his forehead too. The last of the evening sun lit the room. It bounced off my parents’ mirror and made a rhombus rainbow on the carpet. “Maybe he just needs a story.” I thought back to the ones Mom used to tell us before we went to bed. “How about the Elephant in the Mountain? ”

“Can I tell it to him? ” Ally sat on the bed next to the rocking chair.

I nodded.

“Once upon a time, in a faraway land, there lived a herd of elephants. And because the elephants had five toes instead of four, they were Asian elephants. And so the faraway land had to be somewhere in Asia.”

“Ally, that’s not part of the story.”

“Mom always adds things to her stories. I’ll get all the important stuff in.”

“Fine, keep going,” I said. Eric still had tears in his eyes but his cries got a little less loud.

“In this faraway land in Asia, a new elephant had been born. A very special elephant. His name was Om, and he was born the day the sun hid behind the moon. The elder elephants said it was a day of great fortune, but they changed their minds a little while later when they realized something about the new elephant. Om tripped over the ground much more than any other young elephant. And, although, Om always tried to keep his trunk in contact with his mother, Radha, he kept running into her legs. If Om lost contact with Radha, he’d wander, and accidentally get kicked by the other elephants.

‘An elephant that can’t see won’t survive,’ the elder elephants said to Radha.

‘He will, as long as I love him,’ Radha said.

And so Radha only let Om walk underneath her to protect him. Om learned to walk within her four legs, and then learned to walk behind his mother holding her tail with his trunk. The only place where Radha didn’t have to guide Om was in the water. The large pond was Om’s favourite place. He was clumsy everywhere else, but in the water he could feel all around himself and swam easily. Om could spend all day at the pond—he liked to shoot the water out of his trunk as high up in the air as he could, and then feel the water fall down on him.

But Om’s happiness didn’t last long. It hadn’t rained in a very long time, and each day the large pond shrunk a little bit. Eventually the water turned muddy, and at different times in the day many other animals, from the deer to the monkeys, huddled around the edge to drink. Even the tiger, who kept to himself most times, came out to sip the water. Radha noticed the way the tiger eyed Om, and she made sure when he came to the pond there were other elephants around.

The elder elephants told the herd it was time to move on, to cross the dry lands to find water. Radha pleaded with the elders, ‘But Om won’t survive such a long journey.’ The elders said, ‘But if we stay we’ll run out of water.’

Radha didn’t know what to do. If she stayed they’d run out of water and she’d have to keep Om safe from the tiger on her own.”

Ally paused the story to glance at Eric—his cries had quieted and with the chair rocking back and forth, he was calm against my shoulder.

“But don’t worry Eric, that’s not how the story ends,” Ally continued. “It wouldn’t be a very good bedtime story if it did. So luckily one of the birds that stood resting on the elephant’s head had overheard Radha. The little golden oriole said, ‘I know where you can find water, but it’s in the mountain and only the birds who can fly visit it. All others who go in never come out.’

‘Please take us there,’ Radha said.

And so before the other elephants left, the three of them went. The golden oriole perched on Radha’s head, and Om held Radha’s tail as usual. They climbed the mountain, but had to stop a few times so Om could keep up.

The oriole stopped them once along the way at a deep hole in the thick stone. ‘The water is down there.’

‘But how do we get to it? ’ Radha said, looking down at the water far below.

‘We have to go to the other side.’

And so they pressed on to the other side of the mountain. Radha soon let Om walk ahead and held her trunk under him, lifting his body to lighten his walk.

When they finally reached the other side, there was a cave that became narrower and narrower. Radha realized she couldn’t take Om any further as the opening was too small.

The oriole flew ahead into the opening of the cavern with the water, and then returned.

‘Is the water through that opening? ’ Radha asked.

‘Yes, but if he goes down there, he won’t be able to get back out. The walls are smooth and run straight down. But there is an island in the middle that’s shaped like an egg and big enough for an elephant to live on. And light gets in through the hole we saw.’

Om didn’t want to leave his mother. It was difficult for Radha as well, knowing she was sending Om somewhere she couldn’t follow. But she told him, ‘My love will keep you alive.’

Om walked further into the cave and was just small enough to squeeze through the hole in the rock.

Radha heard a splash a few seconds later, and got worried, but when she heard laughter and saw water trickling down from the hole, she knew he was okay.

That day Om sprayed so much water up into the air, the mist rose from the hole, and a rainbow formed over the mountain.

Radha visited him often, gathering leaves and fruit and dropping them down the hole.

The golden oriole told the other birds of the elephant in the mountain, and the birds told the monkeys and other animals. Whenever they passed by the hole they would drop some fruit or leaves down the hole.

As time passed, a stream of water flowed out from the cave. This stream grew stronger as the years passed and ran down the mountain even in the driest days when there was no rain. All the animals drank and also thanked the elephant below by sharing their food with him.”

Ally stopped the story and motioned with her hand against her tilted head that Eric was asleep. As I laid Eric back into his crib, I thought of him dreaming of the elephants, like we had when we were younger. I pictured the elephant in the mountain then, and thought again about what kept him alive.

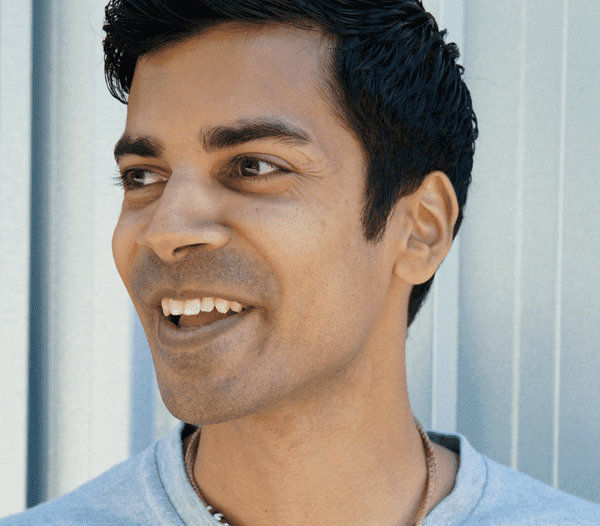

Emerging Author of the Month: Derek Mascarenhas

Tell us about yourself.

Writer. Analyst. Astronaut. I’m only two of the three, but I’ve always wanted to write a story set in space. Maybe after my current project is complete.

Tell us about the piece you’ve decided to share.

I started The Elephant in the Mountain a few years ago in a creative writing course at University of Toronto, taught by Michael Winter. I only recently finished it and gave it to my mother for her birthday. Like most of the stories in the collection, it’s told from the perspective of two siblings, Aiden and Ally.

When and why did you realize you had a passion for writing?

It came gradually. I’ve always loved stories and reading, but growing up I was much more comfortable amongst numbers. Today I try to balance my right and left brain tendencies, but I still think the way I started writing was somewhat analytical—it wasn’t until a couple of years after university that anything recognizable as a story really started emerging. It was around this time I decided to pack up and go on a rather ambitious backpacking trip around the world. In many ways that trip was a catalyst for my writing. I kept a journal the whole way and soon realized I looked forward to scribbling my thoughts on the day’s events as much as the actual day’s events. To go on that trip, at the time I gave up a very good job, but looking back on it now, it shaped a lot of who I am as a person. I view writing in a similar way—something you have to scratch, claw, sacrifice and save to be able to do, but is well worth it in the end.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

There are many. Early on, Farley Mowat’s Lost in the Barrens was probably the first book I felt truly immersed in the world the author created. Roald Dahl is another author who it seems like I’ve been reading throughout my life. I love how playful and inventive his children’s books are, and later found out how brilliant his short stories are. I remember I came across The Wonderful World of Henry Sugar and Six More in a tiny used bookstore in Southeast Asia, and devoured it soon after. It was one book I couldn’t bear to trade, and carried it with me the rest of the journey—I still hide my passport in it on my bookshelf (but might have to move it now). Another author whose work changed both my appreciation and approach to short stories is Alice Munro—she really showed me what’s possible with the art form. I also have to mention Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance. I remember reading that book while in university (instead of my textbooks) and being both transported to Bombay, and utterly moved by the characters; it remains my favourite novel.

What kind of writer do you aspire to be?

A damn good one.

How and when do you find time to write?

How: With much difficulty. Juggling life’s demands is hard enough, but writing is like trying to juggle while someone is whispering in your ear and poking you in the ribs. Every once in a while though, if you’re lucky, you get a pat on the back.

When: I often write late at night. Although it isn’t the most compatible with a full-time day job, I find there’s something about this time that let’s my subconscious run free. Usually it’ll be an image or a line of dialogue that gets stuck in my head; it’s my job to get it out before it drives me crazy, or worse, disappears.

Death Do You Part

It is a cliché dark and stormy type of evening; a girl is running down a path that stems from a dirt road.

Girl: She is fairly tall, 5’7’’-5’8’’; thin, perhaps slightly emaciated but not shapeless; long and unkempt golden blonde hair, damp and matted from the rain, stringy and in her face; large, sunken hazel eyes which are red-rimmed and bloodshot (possibly from crying, possibly from fatigue), pre-orbital dark circles add to her haunted, wild-eyed look. She is adorned in older, faded jeans which are a size or two too big and a heavy, hooded sweater (possibly sporting the logo of a rock band) and worn sneakers.

The girl, who is visibly distraught, disoriented and drunk, is being pursued by a boy her own age. The boy parks his compact sports car and leaves the door open with the engine running. He chases the girl down the path, calling her name:

“Emily? EMILY!”

Boy: he is tall, about 5’11’’-6’’ with an athletic and muscular build; handsome; dark brown hair which is damp and flattened, light blue eyes, wide with panic and concern for his female friend. He is wearing jeans and a college football style leather jacket over a nice sweater, and running shoes.

The girl, Emily, runs faster and harder now, knowing that she is being followed. She wonders:

How the hell did Cameron know I came down here? Did my parents tell him? How did they know?

Emily knows that if she keeps running, she can stay ahead of Cameron. She is almost there.

The path becomes more narrow and overgrown as the boy and girl run on. Emily stumbles and trips over the overgrown grass and rocks. They go for almost a quarter of a km until Emily reaches the train bridge.

The bridge looms monstrously above the little valley like area with the trail and the dirt road that ends at the bottom of a large hill. The train bridge spans several hundred, perhaps even a couple thousand metres above Emily’s head.

Emily feels brave; drunkenly and on an adrenaline high she begins to climb the trusses. She hears Cameron continuously shouting her name and she feels annoyed. And also panicked. This is it.

In thought: I am sorry, Cam. But you won’t bring me back and I am NOT coming down. Not until I get to the top; then I will REALLY come down.

She has to get up there and do it. Emily is determined. Not even the person she loves can stop her.

By the time Cameron gets to the bridge Emily, surefooted even in her drunken state, is halfway to the tracks at the very top. Cameron—your typical “tough and manly” kind of guy—is not without emotion or a heart; he is almost in tears, frightened out of his wits.

“Emily, for God’s sake! Climb down! Come to me! Let me hold you! Talk to me, baby! Don’t do this!! Your mom called the pol-”

Emily has heard enough; she has climbed high enough. At this point she leans back. Cameron screams from below.

“Emily! CHRIST, NO!”

Emily lets her left foot swing back. Cameron’s cries are just unintelligible noise to her now. Her left hand let’s go. Emily smiles now. And everything finally feels alright to her. She feels like she has a repair ticket in her hand and as soon as that remaining hand lets go of the rusting metal truss, she will be fixed.

Emily’s right hand let’s go. She plummets.

Emily shoots upright in bed. She looks around.

The white sheets, the white walls. Her white t-shirt and grey sweat pants. The barred hospital window, showing the outside world of “sane” folk.

It was a dream.

Iliffe Pepper

It was a grey morning in south London to say the least. The sky had heavy anxious clouds sitting in it. It was as if they were doing everything they could to keep the rain inside their pregnant bellies. Occasionally, men wearing smart suits and worried expressions would hurry by, checking their watches as if to say “I hope I can catch the tube to city on time today.” An elderly woman was sitting on her tiny porch clutching a morning coffee and a dog was echoing a fellow canine down the block.

She had been planning on sleeping in a bit this morning, but was rudely awakened by the off-pitch shrieks that bounced around her neighbour’s shower walls and into every flat in the apartment. She groggily swung her feet over the edge of her tiny bed, took about five steps to reach the door, and walked out into the hallway of the third and top floor. She bent over to pick up a small bundle of letters in front of her door. “Looks like they’ve mixed up our letters again” she thought to herself, and walked down the hall to the next door, swapping the bundle for a couple of sad envelopes containing bills (most likely). She dragged her tired feet into her disastrous flat and closed the door behind her, not bothering with the lock as usual. She yawned and stretched, still in her pants and ugly woollen jumper, then walked over to her window sill and lit a cigarette. Her bunny was sitting on the sill too. “What? ” she demanded as he stared at her. She sat down next to him and looked out the window. It was a dreary day indeed. The only exciting thing about it was that she had no business to attend to today, except maybe a Sainsbury’s run for some Nutella. It was this sort of day that made people like her quite content.

She put a kettle on the hob, her cigarette lazily hanging from her softly parted lips, then elegantly perched herself on the hard stool she used for painting. She casually looked around her flat. It was very small. She could barely fit another body in it, although occasionally her neighbour from across the hall would visit for a cuppa and a chat. The front door was on the largest wall and two parallel walls grew from its corners. Crammed against one of these walls was her kitchenette. The one opposite was reserved for her easel and paints. These two walls then turned towards one another to make two perfectly angled new walls, which were home to both of her beautiful rain-spattered windows. Right in between these two angled walls was the last wall, opposite the front door. There sat her robin’s egg blue daybed. It was extremely messy. Her entire flat was messy. There were clothes and papers strewn everywhere. There were half empty mugs and tea cups precariously placed on all manner of teetering surfaces. There were even small bowls here and there, which had transformed from food vessels to ash trays.

However, she loved living in her mess. The time that could be spent on cleaning was spent on thinking, which was much more productive in her opinion. It was days like today that she sat around, breathing in stale cigarette smoke, drinking cup after cup of liquorice tea, and thinking. Thinking about life, and about death. Thinking about art and travelling. Thinking about whether or not she had a chance with her music. Or if she would have another Cheezwhiz sandwich for lunch. Or if she should quit smoking. But no, she could never quit smoking because her neighbour across the hall smokes. She often caught her mind meandering to her neighbour across the hall, and thought about them ever becoming more than just neighbours across from each other’s halls. She also thought about the gigs she would play in the next year. Then, she’d get anxious and light another cigarette. They were just frivolous thoughts, really. But some days she would write them down for herself. And some days were days like today.