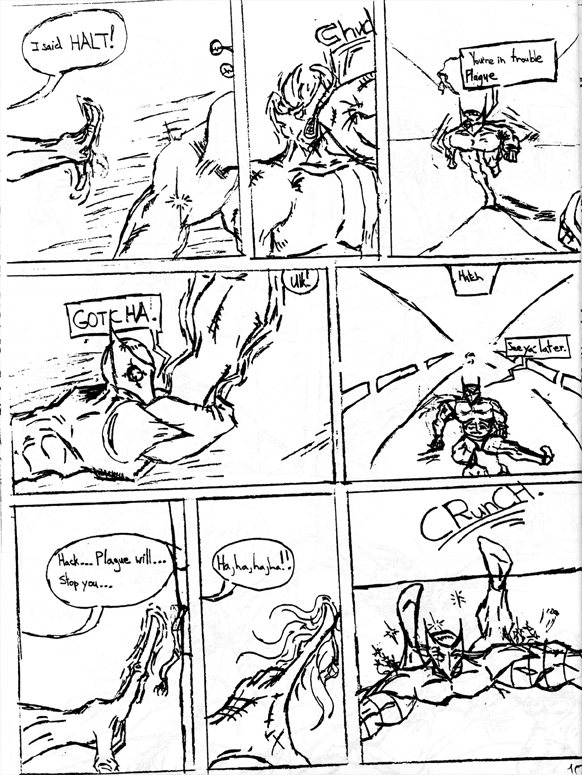

Find a comic book you really like, and select a page or two. Write what happens on the page (or pages) in plain text. Ask a fellow comic illustrator to do the same with a comic he or she likes. Now trade your written descriptions. Draw your friend’s description. This exercise, while it may seem fruitless, is perfect for improving your storytelling abilities. You’re interpreting someone else’s words. And what’s better, you can compare your work at the end to another version of that same written description. Not only will it serve as drawing practice, it forces you to analyze someone else’s drawing as well, so you can see how another artist solved the same drawing problems and handled the same material.

Shorthand

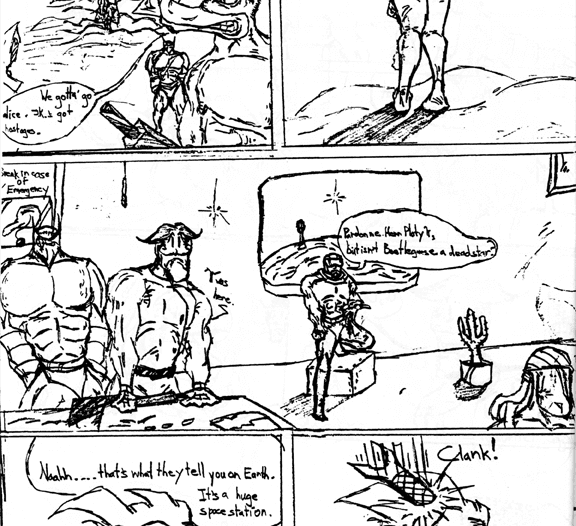

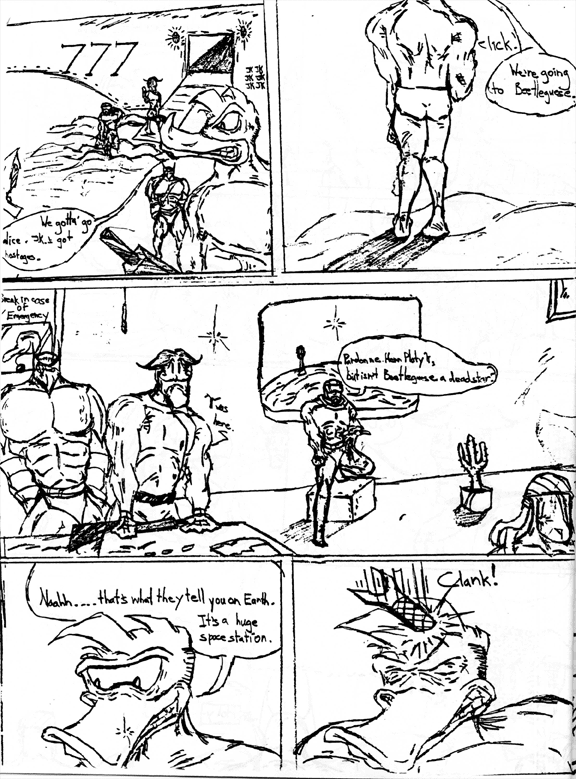

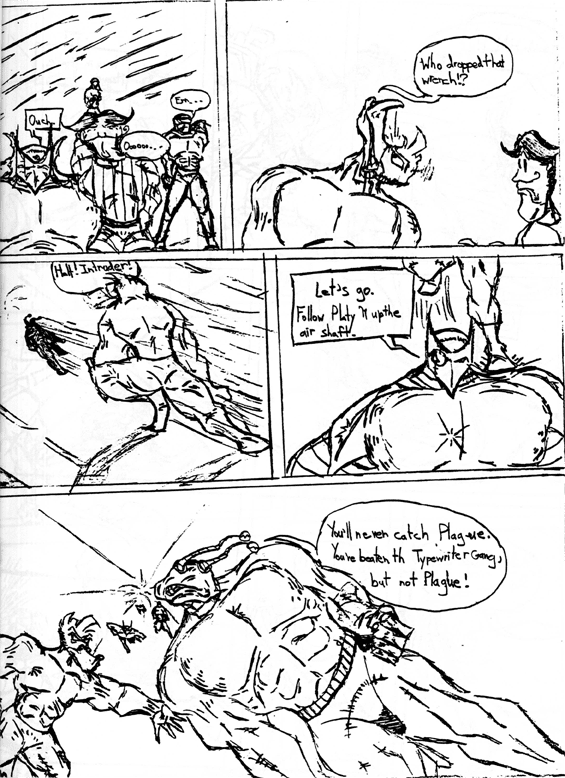

Captain Platy Pi and the Reality Splicers

Author of the Month: Evan Munday

Tell us about yourself.

I am the publicist for Toronto-based publisher Coach House Books. I’m also the author of The Dead Kid Detective Agency, the first book in a juvenile fiction series published by ECW Press. I also make comic books, one of my ongoing projects is about a post-apocalyptic Toronto called Quarter-Life Crisis. And when I have some spare time, I watch only the finest terrible movies.

When did you realize you had a passion for writing?

I think I figured it out around seventh grade. In English class, we’d have to write sentences to demonstrate our understanding of vocabulary words. My sentences grew more elaborate and deranged (frankly) by the week. Eventually, they became full short stories, several pages long that incorporated the vocabulary words somewhere along the line. In retrospect, I wonder if my English teacher disliked me.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

My comic book series Quarter-Life Crisis was hugely influenced by Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim series. I often describe the book as Scott Pilgrim meets Mad Max: succinct and accurate. And The Dead Kid Detective Agency has its roots in the children’s mystery novels of John Bellairs, James Robinson and Paul Smith’s short-lived comic series Leave it to Chance, and the television show Veronica Mars.

That said, I can’t figure out how some of my favourite authors and comic artists have influenced my work. Not in any discernible way anyway. I love Stephen Crane, Michael Chabon, Joe Meno, Kate Beaton—but can I see their work in my own? Not as clearly.

How and when do you find time to write?

I don’t know. If you have any suggestions, I’d love to hear them! I work full-time and as a book publicist, spend many evenings at book launches and readings, so when I write and draw, it’s usually very late at night or on the weekends. Occasionally, I can take a few days off in the winter or summer when the pace of book publicity slows down a bit. Evenings is usually when I write, though. I’m much more of a night person than a morning person, and I’ll sometimes pull all-nighters to finish work. I thought I’d be done with all-nighters after university, but I was very mistaken.

What have been some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced as a writer?

Time is one of the biggest challenges. Writing (or writing well) can take a long time; making comics, even more so. Finding the time to actually write and draw can be difficult, especially when, say, sleeping is so much more enjoyable. I’ve also found that whatever I do, I try to skirt the line between writing for children and writing for adults. My comic books are for adults, but there’s no real reason why kids wouldn’t enjoy them too (I hope). And my children’s novels are also written with adult readers in mind. But making novels or comics that are satisfying to both age groups can be a weird challenge, as you attempt to see how far you can push things without censoring yourself.

How have you changed as a writer over the years?

I used to write and make comics with a definite point or goal or theme in mind. The theme came first and everything I wrote was to help define and augment that point. Almost like writing an essay in the form of fiction. Gradually, that’s changed, so that I now just try to write a good story. After a couple drafts, I then figure out what themes I’ve been grappling with (subconsciously) and work to pull them out a bit. With the second book of Quarter-Life Crisis (which I’m currently working on), there was about a year between first writing the script and me figuring out what idea the story was engaging in.

Sisters Always

For as long as I can remember I’ve always wanted sisters or even just a sister, singular, but never had one because of circumstances clearly beyond my control. I’m uncertain of the origin of this desire since I had a full childhood and a fun brother, but nevertheless, I’ve always wanted, nay, desperately dreamed of how great having a sister would be.

There were four of us in high school who were really close best friends and we all referred to each other as sisters. We would sign birthday cards with love, your sister so-and-so and we even had silver rings engraved with Sisters Always, when we were still young enough for that kind of thing to be sweet. However, we all eventually lost or broke the rings. Plus, at different points each of us began to choose deadbeat boyfriends over each other, damaging our relationships in ways that made us start to resent each other instead of unconditionally loving each other, which by the definition I go by, is what being a real sister is all about.

The demise of the jewelry could be considered a foreshadowing of the fate of our sisterly relationships with each other, because I’ve since cut my losses in that department with them. I still love them as friends, just not quite like sisters. Sisters! Even the word fills me with longing. Staying up cross-legged on each others’ beds too late on a Tuesday. Fighting to the death over who gets the pancake with the most chocolate chips!

I’m over it.

So when I met Sara through a mutual friend and we decided to get an apartment together at the end of the summer, because neither of us could afford living on our own, in the back of my mind I thought maybe, just maybe, we would grow to have the type of sisterly relationship that didn’t need the affirmation of matching ring engravings.

After all, we had all the makings of a sisterhood because of all the things we had in common. We looked like each other because we are both Dutch, although she is a bit more so because she was born over there, whereas I am representative by last name and gene expression only. We both liked the same kind of films (Spanish stuff and whatever Audrey did) and we even slept with the same guy, although at different times, which was a small factoid we discovered one night after a few whiskey-waters and half a pack of cigarettes. Perfect!

Not long after we moved in, however, I found out a bit of information that essentially ruined everything. Sara already had five sisters. Five. I didn’t know that was even possible.

Of all the things in life she needed, or perhaps didn’t need but wanted, a sister was not one of them. I didn’t even have to ask to know that for sure.

Sara was the youngest of her sisters, Geertje, Doutzin, twins Yopi and Jacoba, and Roos. This made things worse for me because Dutch names are impossible to pronounce, punctuating not only my longing for a sister, but also my cultural shame for not being able to speak the language and so, by default, throwing out my ancestry in the garbage dump of life.

I was always relieved when Roos called because hers was the only name I could pronounce with confidence, as it had only one syllable. Every time she called, I would make a big fanfare of it, going all “Hey Sar” – which is what I call Sara—“Hey Sar, Roos is on the phone!” She’d be all like, “What?!” and I’d go: “Roos. Roos. ROOOOS!”

I had to stop that after a while though, because I didn’t want either of them to get the idea that I liked Roos in a romantic way, which would have been a perfectly reasonable deduction considering all the fuss I made every time she called.

In any case, I had to essentially accept that Sara and I were never really going to be sisters, since bottom line was she had so many already.

I moved on.

Eventually, October rolled around, which meant that Thanksgiving was upcoming and since my family lives far from the city, it was looking like it would be a solo holiday for me.

Then one morning, I was frying Sara and I some delicious eggs while she struggled with the notoriously stiff plunger of the French press in the kitchen.

“Oh, I forgot to ask you! Thanksgiving! You should totally come to my family’s house with me.”

My ears felt hot, but I played it cool.

“Yeah, totally, I’m there.” I flipped the eggs really high, which is a neat trick I can do.

“What should I bring?”

The eggs landed perfectly on the inner rim of the pan and slid to rest in the centre. Still got it.

“Oh please! Just come.”

Sara scratched an itch on her upper lip and left a smear of wet coffee grounds right across her face that looked like a huge moustache. I turned her around so she could see her reflection in the microwave. We both laughed our heads off.

I was really good about not getting my hopes up, but still, Thanksgiving was shaping up to be amazing.

When we arrived and I saw her whole family with all those sisters for the first time, it really hit me how many of them there really were.

It turned out that the twin sisters, Yopi and Jacoba, were both not only expecting babies, but were both in the same term of pregnancy which was quite a sight, if you can imagine. They were like twin planets orbiting around everyone in the living room, or we were the ones orbiting around them. It was hard to tell.

Geertje, the eldest, was definitely the most hardcore because she rode a motorcycle to the party and consequently owned and wore a disproportionate amount of leather from the rest of the family. Also, she had a tattoo of a bird of prey on her forearm.

Doutzin, the artsy one, was projected live from her apartment in Antwerp on the TV all day via some internet feed, which I found very futuristic although everyone else thought it was normal.

And then there was Roos.

Roos is the black sheep of Sara’s family, which I didn’t realize until I saw them all in a room together and Roos was the one in the corner with her shoulders hunched, wearing an exaggerated frown.

All six sisters, Sara included, were tall and beautiful with green eyes and sandy blonde hair just like both their mother and father. My Nan used to say: “When a man has multiple beautiful daughters it means he must have screwed over a lot of women in a previous life.”

Not that I believe that, I’m just saying.

After the rest of their extended family arrived, card tables were stacked end to end starting from the kitchen and making its way down the hall and into the living room. Some of the small kids had to share chairs and the cranberry sauce was kept in a container with a lid so we could launch it like a football down the table to whoever needed it. I sat next to Sara, obviously, although Roos seemed a little irritated about getting bumped one seat down and refused to pass the salt to anyone in protest.

The dinner, itself, surprisingly was fairly uneventful despite the arrangement. The exception of course was Sara’s aunt Helen, who fully farted during grace. Cousin Katie took her home before pie, though, because she was hammered and had fallen asleep. This was disappointing, as one could imagine. She was hilarious.

All throughout dinner, Sara tried to explain who was related to whom, how, and what each person was famous in the family for. It was impossible to remember but entirely rapturous. The joy I felt from the great time we were having made it very difficult to suppress my feelings of wanting to be sisters.

Then, I had a sort of devilish idea. One, that now I’m almost ashamed to admit. What if I lured one of the sisters away from the pack and maybe, just maybe, replaced her? Perhaps we could be sisters after all.

I remembered Roos.

When we finished up dinner, we folded all the tables up and arranged the chairs around the living room.

Since Sara’s family is so large, they have all kinds of traditions when they all get together on holidays. Although I’m not normally an advocate of forced fun, I’d had enough wine by the time the cards, boards and eggs on spoons emerged.

We had a vote for what we’d play.

Judging by her all-performance fleece vest and tight ponytail, Roos was definitely the sporty type and not the artistically inclined type who would excel at a game like the drawing-based Pictionary.

I put my hand way up for Pictionary.

My vote tipped the scales, so Geertje hauled out the chalkboard easel and the coloured chalks. The twins handed out cocktail napkins with little wieners on them, while Sara’s mother put bowls of licorice on the table. Sara’s balding uncle, who was a bit grabby with me earlier, sat down next to me. I made a smooth exit for the punch bowl.

When we all finally congregated in the same room, they asked Roos to host the game.

“Never!” she snapped, recoiling into her turtleneck sweater, so Doutzin took the helm via satellite. We split into two teams of six.

Tempers quickly escalated as they tend to do during Pictionary because of the disparities inherent in the game itself. For instance, one team will get moonwalk and the next team will get Suez Canal. It sucks, but that’s Pictionary.

We played several rounds until our teams were tied and it was Roos’ turn.

“If you win this clue, your team wins the game, sweetie,” her father reminded the whole room.

Roos looked terrified.

She pulled her card and tears started to cloud her eyes, but the family would have none of it. They all cheered her on. The timer started and Roos was stuck up there doodling blobs and trembling.

“House of cards! Trains! Train STATIONS! Bobsled Teams! Jamaica!”

Her team was totally lost, understandably so, because her picture was terrible. But then suddenly, it occurred to me what the lopsided box and swirly doodles were.

Roos’ clue was soap dish.

I looked up at Roos, humiliated, drawing circle after circle, around and around and I started to feel guilty for causing her to be in that position in the first place. Truthfully, she was as sad a soul as I was, just in a different way.

My conscience was in crisis. I realized it wasn’t fair of me to remain silent, even if we weren’t on the same team. So I leaned over and was about to whisper the answer to her cousin, so that she would be saved from her misery. But, just as I was about to speak, my tongue jumped back down my throat and refused to budge.

Roos had won in the game of life up to that point, and it looked like even if rationally I wanted to do the right thing, I was going to cross my hands quietly in my lap instead.

The last grains of sand slipped through the red plastic hourglass and a cacophony of cheers and groans filled the room. Roos’ demise was complete.

Sara’s family’s rules stated that the next team could go for the steal.

“Okay,” Doutzin piped in from the TV screen, “next team?”

“Soap dish!” I shouted.

“Yes . . . ” Roos groaned.

A cacophony of cheers and groans again filled the room.

“Maybe you and Roos here were swapped at birth.”

Geertje held her fist up to tap mine.

I stole a glance at Roos who was shooting eye darts at my head.

The family was too busy clinking glasses in celebration or arguing over the points to notice her slinking out of the room, dragging a greasy butter knife along the wallpaper leaving a huge long mark. Totally weird.

I thought about going after Roos to smooth things over, but then I had visions of her stringing me up and bludgeoning me with a dirty shovel. I decided against it.

By the end of the day, I was absolutely exhausted. As the last of the family trickled out the front door, Sara and I were faced with a kitchen of dishes, followed by the twin-sister planets who each needed help being lowered into and out of their individual baths because their joints were swollen and puffy. Roos was supposed to help, but she was nowhere to be found.

I made a joke about installing the harnesses they use to lower boats in and out of marinas into the bathroom, but neither pregnant sister found it very funny.

“Pass the cucumber face mask,” Yopi sneered.

When we finally got home, I threw myself face first onto my bed and stayed like that with my shoes still on. For the first time since I could remember: the thing I wanted more than anything—even a sister—was to be completely alone in full peace and quiet.

“Wait, don’t fall asleep yet!” Sara pleaded. “Let’s just hang out for a few minutes.”

I gave her my best you’re killing me with a hundred daggers look, but she ignored it.

“Come on, I’ll make tea and we can sit on my bed and smoke out the window.”

I slowly got up off the bed and yawned in the most exaggerated way I could without triggering my lock-jaw.

“Today was fun, thank you so much for inviting me.” I gave her two genuine thumbs up.

“It was,” she agreed, “Come on, just five minutes.”

“I’ll give you something far better than five minutes,” I yawned again.

“What?”

I hugged her and gave her two solid back taps.

“That was it.”

“What?”

“G’night.”

I gently pushed her out of my room and closed and locked the door behind her.

I gathered all my pillows together, curled up and slept like a baby until morning.

Emerging Author of the Month: Marni Van Dyk

Tell us about yourself.

I started to write, like most of us, when I was a hormonal teenager, and I still always smile when I find those tortured typewriter-written poems on scraps in the bottom of drawers. Great, awful stuff. It wasn’t until I was in university that the very influential professor and talented writer Randall Maggs shone a bit of a light on me and challenged me to push myself to write more, and also, to not take myself too seriously. I listened to him and did both things which I think are equally as important. After graduating, I co-founded the all-female sketch comedy group She Said What with my closest and funniest friends. The project has gone on to do quite well, I’m happy to report that it was nominated for a Canadian Comedy Award among other successes. Creating SSW was a critical point, because we were creating work for ourselves at a time when no one was knocking on our doors offering us any. We became much stronger writers by going through the sometimes arduous process of creating countless stage shows together. You knew right away in that arena if you’ve written something good or not. While writing sketch comedy, I also have been working with an educational institution that takes students overseas to study on location—think studying Roman Gladiators at the Colosseum or the French Revolution at Versailles. I’ve traveled extensively, lectured, performed and written a lot of academic content and held workshops aimed at getting students engaged and excited about the world around them. Most recently, I’ve also been writing for, and playing the role of the “comedic” co-host of a car show airing in the U.S. and the U.K. where I get to ride absurdly fabulous cars and then make fun of them. It’s a tough gig. Also, I’m currently working on my first collection of short stories. The first story from the collection “The Red Mouths” is set to be published in subTerrain magazine.

Tell us about the piece you’ve decided to share.

Sisters Always is a character driven piece that takes a sort of satirical/comical look at how small wants or longings can transform into strange obsessions. In the era of shows like Hoarders and My Strange Addiction, I think we’ve come to understand that really anything is possible and we all have a bit of strangeness in us in some way or another. In a way, I hope, this story touches on that point just a bit. The narrator is consumed with the idea of having a sister, so much so, that it colours her approach to having any sort of relationship with other women. It’s definitely a hyperbole meant to be funny or heaven forbid, silly, and I think it reflects that weird obsessive side we all have but would rather not share publicly. Whether it’s cutting your cuticles, collecting fridge magnets or compulsively applying hand sanitizer, we’re all a bit odd.

When and why did you realize you had a passion for writing?

I don’t know if I ever realized I had a passion for writing as much as a passion for story-telling. I grew up in theatre and dance and the idea of communicating ideas and connecting with others’ experiences through stories, both with and without words, has always been prominent for me. Writing my own stories, whether for stage or the page, was a natural evolution of telling others’ stories through performance.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

Ann-Marie McDonald’s Fall on your Knees. The book is brilliant, no doubt, but for me it was the first time I had read a story where there were so many female characters that were so fascinating, complicated and fully realized in a way that made me see the possibilities in writing for myself. All of the books I read growing up, particularly in school, were about men and boys coming-of-age told through the eyes of men. Reading Fall on your Knees was a revelation for me. Junot Diaz also had a huge impact on me in terms of finding character voice and putting forth the idea to share the kinds of stories we aren’t, but should be telling. I’m also a huge fan of Dave Eggers, Joan Didion, Raymond Carver, Michael Ondaatje, Anne Carson and, of course, Gabriel Garcia Márquez.

What kind of writer do you aspire to be?

A good one?

How and when do you find time to write?

When I’m well-rested, have some alone time and a bottle of wine. Translation: not as often as I’d like. Keeping a notebook on you at all times is helpful however.

One by One by One

It began with the birds, Icarus-winged, high and fast, far reaching towards the sunset, a reckless dance that swam upon the evening breeze. Starling cloud storms thundered westwards; squawking gulls, twisting and circling, cackled across the thrashing sea. The barn owls flew their perches; the falcons fled the chalk white rocks. Not one pigeon remained on the cold cut stones of Trafalgar Square; not one pheasant lay to roost, grain fat and weary, in the dank and dreary fields of a single country estate.

The people mused, confused, butchers and bakers, cashiers and clerks. Their theories mounted, their solutions babbled and gushed, the world to rights was put upon the public plate of resolution, and they went on, they moved on, they were dismissive and curt. They made do without poultry, for there was plenty of fish in the sea, and cattle upon the land, and grain in the fields. They made do without pigeons, for there were radio antennae and telegram wires. They made do without pheasant and quail and grouse, for there were foxes and rabbits and even stag to hunt too. Life moved on, clicked-but-not-clucked on, and the people built bigger farms to raise the cattle and bigger nets to trawl the seas, and they soon forgot what they had lost.

Time moved on, and there came a day a while later when the fishermen came to market with empty carts. The people asked for herring and carp and haddock and cod, but the fishermen had nothing but saltwater and broken nets. They trawled the waves for days and days with no avail; the fish had gone. The herring and carp, the haddock and cod, tench, trout and turbot, all had departed. The streams and estuaries, the rivers, brooks and the heaving seas that whipped and snapped at the sandy shore, all were barren, all were dead. The people asked for answers, they asked the politicians, the policemen, the publicans and the preachers, but none could speak, none could even mutter. A desperate few turned to God, (but she rarely offers reprieve to folks at times such as these).

So they went on, they moved on, dismissive as always and curt. They made do without fish because there were plenty of cattle upon the land; there was plenty of grain in the fields. They made do without cod and chips, and kippers for breakfast, they made do without plant food and finings for the ale. There was always pie and sausage and compost and lager. Life moved on, mucked on, from the fields plucked on, and the people built bigger and better farms, and bigger and better factories, with bigger and better yields, and they soon forgot what they had lost.

Time moved on, swiftly on, as time does at such a time. Soon enough the fields overwhelmed with cattle, and the fens run over with sheep, and the pens brimming and brining with swine, could hold a beast no more. The fences creaked and swayed and yearned, they cracked and sprung and squeaked. The farmers braced against the flow, and the fishermen who’d turned to meat, and then the politicians who’d no other fish to fry, and the preachers (who had nothing to eat). And the fences bulged and burst and broke and the beasts, each one ran free, and knowing, somehow, which way to run, all headed for the sea. The sheep, pigs and bovine, the horses and dogs all flew, and the rabbits and stag, all the beasts of the land, ran swift along with them too.

The people stared in wonder. Not a soul was the least amused. They stood and strained towards what they had lost beneath the great deluge. The worshippers cried for vengeance, but against whom they couldn’t decide, most people just pretended to grumble, then secretly went home and cried.

But they went on, they moved on, forever dismissive and curt, it did not matter in the least little bit how much this catastrophe hurt. They made do without pork and beef, and lamb and mutton and veal; without Sunday roasts and pheasant shoots and sausage and jellied eel; no chicken coops with farm fresh eggs, no cock’s crow in the morning; no dogs to bark in the dead of night to give their masters a warning.

There was plenty of grain in the fields, there was bread and beer and honey; there was cabbage and carrots and turnip and yam, so there wasn’t a need to worry. The preachers and policemen tilled the fields, the farmers and farriers too; even the butchers lent a weary hand (for they had nothing else to do). And soon the fields burst and bloomed with life, they supped on bread and honey and beer, they drank and they sang and forgot what they’d lost because now they had nothing to fear.

And right on time the time moved on, for time is like that when there’s things to go wrong. For one fine day in grey September, as the harvest was carried from the fields, and the pickers and preachers and politics-men were hooraying about the big yields; the worms slid up from the brown patchwork ground and squirmed their way to the shore, and the leeches and beetles and bugs followed on, and many a creature more. The ants and termites and lice and ticks, the wasps, the spiders and fleas, every insect, arachnid and slithering thing, oh, and of course the bees.

So the people moved on, mucked on, blind and deaf they all trucked on. They dithered and blithered and ever dismissed, they feigned to wallow in ignorant bliss. They bumbled and grumbled and eventually cried, then tried to stay curt through tear stained eyes. They made do without honey for a while, they tried and failed to shrug and smile. The winter came in swift and strong, and before too long the grain stores ran low, and the last of the pickles and preserves were scraped from the last glass jars onto the last thin crusts of dry, flaking, butterless bread. The spring rains brought no new shoots; no crops spread their roots in the barren fields. There were no birds and bees, because the bees and the birds were gone. There was no pollination, no propagation, and no final reprieve. By now there was nothing left to do, there was no thing to relieve, so all the people hungered and the people wondered why, and the people tried to figure out what had gone so terribly awry.

And the time moved on, the sands sifted down. The people slinked and shuffled about, their muffled groans offered no new plans; their leaders gave up giving commands. They scratched at rotten tree bark and discarded feather, they chewed on threads and suckled on stone. Soon skulking eyes flashed one to the other; the people craved flesh and bone. The weak began to falter, the old stumbled and swayed, and neither could keep one quaking foot out of the bloody grave. When one fell, the rest fell upon them, tentative at first, a bite and a tear, but the ravenous teeth took hold and before long the unthinkable became thought, heredity and pride reduced to naught. They went on, moved on, but now they weren’t quite so dismissive, and there wasn’t much point in being curt. Soon to be mothers became sick and more weary, unborn children, sensing too well their dreary futility miscarried themselves, their bodies roasted over coal fires, while their bloodied mothers wailed in grief and hunger and soon too were dragged lifeless to the cooking embers, picked to the bone like boiled chicken, giblets and all.

So one by one the publicans, preachers and policemen, the farriers, farmers and fisherman’s wives, one by one the bakers, butchers, clerks, cobblers, cooks, the vicars and the village idiots, one by one the salted sea captains, dashing squires and their coy mistresses, one by one the milk maids, mothers, children and school-house teachers, one by one the grooms and their blushing brides. One by one, the people cut, killed, or starved, and one by one they all died.

The last man had wandered the carrion fields plucking through the scattered bones for food. He had walked past the breached and broken fence posts and the dry and salt-smelling fishermen’s nets. He had stalked along the shore, skimming stones at the black, thrashing sea. It was night-time, and the sky was dark as pitch when the last man stopped looking for food. There was none to be found the last day, and no doubt there’d be none still the next. The man sat down on the sands, staring east across the sea. The smoking coal fires had blotted out the stars; his eyes stung. As he waited there for death’s embrace, tears began to stream down his blistered cheeks, drowning him in the memory of all that was lost. He wailed with all his waning might into the darkness, it was the last song of sorrow.

As the last man sung his last refrain, and his soul melted into the sand, he saw the dawn scratch its chalky line across the far horizon. Shards of silver flashed across dark water, and in the distance, shadowy against the fragile morning’s light, the last man saw with his last shred of sight a silhouette leap across the yawning sun: It was Icarus, twisting and tumbling in the sky amid a flock of starlings. He danced on the wind, catching the shadows with his tapered wing, and headed shore bound on the soft morning’s breeze.