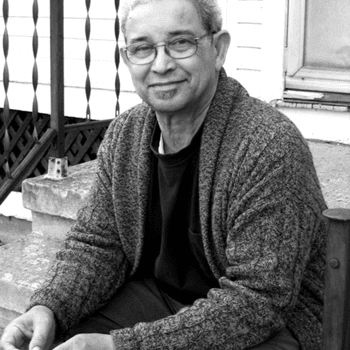

Tell us about yourself.

I was born in Madras, India, and I have lived in Dubai, Banff, Toronto, Oxford, and Benares; I like to think of myself as a bit of a nomad, most at home on the move, in meadows and on mountains, at the meeting places of misfits. I’ve studied psychology, religion, social work, and international development, and for the past few years I’ve been trying to find ways of balancing my interests in social justice and literature through my writing and activism. In 2011, I was a finalist for the Guardian’s International Development Journalism Competition, for which I spent a week researching a story in Manila. More recently, an essay I wrote on religion, freedom, and economic development was awarded the Ngo Human Welfare Prize by Green Templeton College at the University of Oxford.

Tell us about the piece you’ve decided to share.

I’m sharing two excerpts from my novel, Nostaglia for the Future, which follows the life of Christina Fleischer during her teenage and student years in Toronto between the late 80s and early 2000s. Through its depiction of Christina’s search for meaning and a moral anchor, the novel explores what it means to be a young Canadian in a world where old certainties and truths are increasingly liable to question. Christina must learn to navigate the complex interplay of politics, religion, and morality in order to come to a realization of the possibilities inherent in the experiment of hope that modern multicultural Canada represents, even as she faces the dangers and misunderstandings that arise from the cultural conflicts she encounters.

Christina, a teenager of German-Canadian descent, befriends Fatima Al Akbar as they start high school together in downtown Toronto. The only child of a misanthropic academic and idealistic artist, with a tendency to escape the world around her by turning to books, Christina is drawn to Fatima, an orthodox Muslim of Palestinian-Egyptian heritage with a similarly literary bent, as they recognize that they both feel like outsiders, albeit in very different ways. Christina becomes a frequent visitor in Fatima’s home, where she is welcomed with warmth and generosity into the Al Akbar household by Umm, the matriarch and helm of the family, whose kitchen and songs become the anchor of their childhood. Not long after she gets to know the family, Fatima’s older brother Sharif, and later her younger brother Karim, are sent off to Afghanistan to join their father in the fight against the Communists, and as Fatima approaches her final year in high school, she and her mother join the rest of the family in Afghanistan. In the years that follow, Christina progresses through her studies in university, increasingly bewildered by the news emanating from the Middle East, tensions in her own family life begin to increase with the death of the other source of a spiritual anchor for Christina, her grandfather, a scientist who had moved from Germany to Canada after the Second World War. The letter he leaves for Christina at his death throws her into turmoil as she tries to reconcile the gentle old man she knew with what she reads in his last words to her. Christina’s liberal, questioning parents give her little certainty to hold on to in her quest for a moral centre, and her struggles come to a head in 2002, when Umm, Fatima, and Fatima’s youngest brother Saif, return to Canada to seek medical care for Saif, now grievously wounded in battle.

The first piece is from the beginning of the novel, just after Christina has got to know Fatima; the second is set ten years later, some years after Fatima and her family have left for Afghanistan.

When and why did you realize you had a passion for writing?

I’ve always read a lot and over the years became increasingly fascinated with the ways in which literature could have an impact on people’s lives and provide alternate ways of envisaging solutions to political and socio-economic problems through the creation of empathy. I was initially drawn to writing because of an urge to tell stories in a way that might help people enter into lives that are not their own and see something of themselves in others. The silence and solitude of a writer’s existence have also always attracted me, and over the years, writing has become a means of processing life and approaching stillness. Having studied social work and international development, I decided to return to creative writing as a more empathetic way of approaching the same goals of thinking about the larger moral issues of modern life.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

I’ve often returned to the works of John Steinbeck, Seamus Heaney and Halldór Laxness for their largesse of vision and the respect and sympathy with which they depicted the lives of the poor and disenfranchised. It was in reading them that I first sensed the transformative power of narrative and verse. Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead has also been a very special book for me because of the meditative nature of its prose and the fearlessness with which it approaches the immortal.

Canadian authors have also been influential in the development of my literary consciousness. In particular, I have admired the works of Gwendolyn MacEwen, Margaret Laurence, Mordecai Richler, Alistair MacLeod, Tomson Highway, Joy Kogawa, and Elizabeth Hay for their capacity to hold a mirror to the Canadian psyche and create a new mythology for Canada.

What kind of writer do you aspire to be?

I want to be a writer who can’t be put into a box. I hope my writing will address the perennial questions of human existence, across many genres, including fiction and non-fiction.

How and when do you find time to write?

I like to write in the mornings when I am bleary-eyed and still in my pajamas, before the distractions of the world have a chance to intrude. When I am lucky I also retreat to cottage country and write staring off at a lake.