Come one, come all, gather round, take a seat, And let me show you the latest technological treat. Is your world awfully dull, grey-washed and boring? Do you find yourself sitting in class, at work, snoring? Are you counting the days and filling your time Waiting for death in an orderly line? Fear not my friend, my darling, my dear, Pirelli’s new glasses are finally here! A volunteer? A Jane? A Jack, Jill or John? Ah, there you go, just pop these specs on! See there’s a filter inside that makes it all rosy, Pastel and pink, softened and cozy. Isn’t that better? Isn’t that grand? But wait there’s more; let me give you a hand! With the push of this button your view will all change, And your world can be wonderfully twisted and strange. This button right here can switch it around, Make everything vintage, aged and tea-browned. One more switch and you’ll see colour all gone, Like an old classic movie, your show must go on! The photos you look at, the TV you see, Has all been altered for you and me. And if all that is faked, airbrushed and pretty, Why should life have to be realistically gritty? So why don’t you buy a pair or a dozen? One for yourself, your mother, your cousin! I’ve got plenty here for all who can pay. A drop in the hat, now wouldn’t you say? Come one, come all, gather round, spend a dollar, And let Pirelli create splendour from squalor!

Shorthand

Ruminating

In ere of a dream, I am not but ruminating. Yet, is not life that deceives me; instead it is the merit of love. For the stars are not in my eyes, and cordiality is lost in my voice. To this, I so ever conjure, if I merit perfection. For in her delicacy, she paints her face on the sun, And in her mind, mermaids sail in the sky. But I, just a lowly man should be ignorant of this love. That a beauty of this sort should surrender to devotion. Yet, as I lay, encompassed without justification. This same angel takes my hand to heaven.

It’s All in the Details

When I was a journalism student at Carleton University, the big media outlets would come around once a year to conduct job interviews. A famous interviewer tactic was to ask the interviewee to look out the window and name five ideas for news stories. One student made a study of the view outside the building before his interview and went in with five weighty, hot-button ideas all prepared. Sure enough, the interviewing editor asked him to look out the window, but when the student turned away from him to look, the editor asked “What am I wearing?“ The student had been too busy rehearsing the story ideas inside his head to notice what the editor was wearing and had no answer.

Writing isn’t about what you’re feeling or even what you’re thinking. It’s about what you see (and smell, and taste, and hear). If you’re just starting out, or are between story ideas, make a point of writing one descriptive paragraph a day: describe a house or a garden that fascinates you, describe a fabulous (or a terrible) meal, or a bar-by-bar description of a piece of music. Forget about why you think the subject is interesting, or how it makes you feel; let the details do the talking and keep your description concrete. Keep your paragraphs in a notebook. You never know when they’ll come in handy.

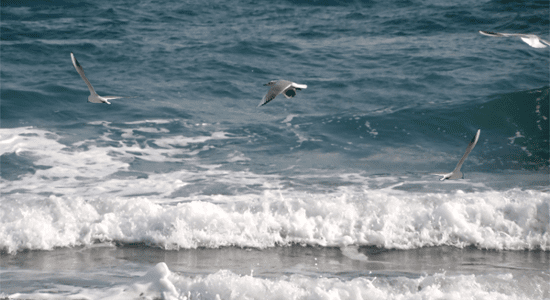

From By the Bath House

The whitecaps rolled and curled to crash skywards off the breakwater. Looking up the shore in the other direction, you could see the Castrol GTX sign flashing green, white, red, 6:30, 15 degrees Cº, just as it had always done. When you came for mood walks on fall afternoons and summer evenings, when you made love in those pungent alcoves, the taste of beer, someone vomiting off the lifeguard tower and now with Eddy, the sign kept flashing. Underneath it, the streetcars rolled past the Edgewater Hotel. You could hear the hollow metallic rush of their wheels, the day’s first factory workers impaled on their seats.

Castrol GTX . . . green . . . white . . . red . . . it is seven o’clock . . . it’s 14.7 degrees Cº.

“Eddy? ”

“Hunh? ”

“They say that every seven years things change. Do you think that’s true? ”

“Maybe.” Eddy sunk his head deeper into the blanket and ran his hand up her thigh.

Janice looked back out at the lake. Whitecaps rolled and curled against the breakwater, shattering into foamy globules. Seagulls leapt upwards to bob and hover, bob and hover. Shadows slipped out of the Edgewater Hotel to be absorbed by rolling wheels while, above, Castrol GTX time clicked to degrees centigrade. Every seven years. She ran her hand up from the bronzed base of Eddy’s back, between the broad blades of shoulders and beneath gilded curls to the band of his neck. She squeezed, thumb and forefinger over a pulsating jugular.

But then thumb and forefinger sprang away and her hand hung lifeless over the prone figure. Eddy stirred, moaned, and fell asleep again. Janice turned away, drawing her knees to her chin. There was an empty bottle on the blanket next to her. An involuntary spasm sent hand to bottle and girl to feet. And then she was whirling in the sand with a spinning weight of glass in orbit. The bottle, shining and clear, grew weightless and took flight. It smashed against one of the bath house columns and tinkled onto the urine-y sand at its base.

Jan stood motionless, letting the wind send wisps of her hair askew and listening to the seagulls crying, the foam globules crashing. After a few moments, she sat down on the blanket again and put Eddy’s hand back on her thigh. She sat like that for a very long time.

Author of the Month: Andrew K. Borkowski

Tell us about yourself.

I was born and raised in Toronto’s Polish community on Roncesvalles Avenue, studied Journalism and English at Carleton University, spent eight or nine years after that working odd jobs, doing bits of theatre and freelance journalism. I spent two years in England learning how not to write a novel, then came back to Toronto where I settled into making a living as a freelance journalist and editor. I kept writing fiction throughout this time—short stories which began appearing in quarterlies in the late 1990s and eventually evolved into Copernicus Avenue, a collection of linked stories about Roncesvalles which was published by Cormorant Books in 2011 and won the Toronto Book Award in 2012. I’ve pursued music as a sideline, serving as vocalist, keyboard player and occasional song writer for a local blues/jazz ensemble The Grayceful Daddies.

Tell us about the piece you’ve decided to share.

“By the Bath House” is the first story I ever wrote and revised to a finished state. It’s set on Sunnyside Beach in the shadow of the bathing pavilion which, in those days, was in a pretty decrepit state. “Bath House” was never published, but I read a bit of it to a CBC reporter covering an event for would-be authors at the Harbourfront. The clip, and a short interview, was broadcast on CBC Radio’s Morningside. The host at the time was Don Harron, who said “He sounds honest, he sounds dedicated, I think he’ll make it.” The reporter commented that she thought I used too many adjectives.

When did you realize you had a passion for writing?

Very early. At age six I was filling notebooks with half-invented accounts of “My Adventures.” The first time I ever thought I’d like to make a career of writing was on a family visit to the Leacock Home in Orillia when I was about twelve. I remember standing in the room where Stephen Leacock did his writing, in a boat house overlooking Lake Couchiching, and thinking, “This would be a cool way to spend your life—sitting in a place like this, just dreaming things up.” Not long after that, I started writing little science fiction stories which my Grade 8 teacher Mr. Davis would read aloud to the class every Friday afternoon. It made me quite the popular guy.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

D.H. Lawrence was the first “serious” writer I remember having an impact on me. Older people still thought of him as a writer of “dirty books,” but I was turned on by his descriptions of nature and the sheer force and passion of his writing. My high school had a superb English department whose teachers had a knack for turning writers such as J.D. Salinger, Hemingway, and James Joyce into cult figures that rivalled rock stars. Joyce’s Dubliners was a model for Copernicus Avenue. In recent years, I’ve been most influenced by the disciplined style of Raymond Carver, and by the early work of Italo Calvino, which has the whimsical quality of folk tales. I keep going back to Virginia Woolf, and Salman Rushdie, perhaps as an antidote to my minimalist bent. I don’t write anything like them, but I keep hoping they’ll rub off on me.

How and when do you find time to write?

I’ve freelanced for a living my whole career, so I’ve had to fit creative writing into periods between assignments. I like to have periods of at least a week—preferably more, as long as my bank balance will permit—to get up ahead of steam on a creative project. Ideally, I like to have two writing blocks in a day: 2-3 hours in the late morning and 2-3 hours in the late afternoon, with exercise, errands, and occasional lunch meetings in between. The best work usually gets done in the second block, but I need the first one to get the wheels turning. I’m a night owl but not so much for writing. Evenings are for events, reading, correspondence and the little stuff that goes with the business of being a writer.

What has been some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced as a writer?

The biggest challenge is how to keep body and soul together and still find time to write. There’s no easy solution: writing literary fiction doesn’t pay much. For the first decade of my career, I survived on what, today, we’d call “McJobs,” but after a while those menial occupations become mind-numbing. Freelancing as a journalist and editor was my solution; it gives you flexibility, though it requires a lot of your time and energy and it’s not getting easier to earn a living that way. There’s no perfect solution. If I were starting out today, I’d be looking for a career that gave me some stability and bought me an hour’s writing time for every hour on the job. It doesn’t have to be literary or intellectual in nature: carpentry or a private physiotherapy practice might do it—anything that gives you control of your schedule and pays decently.

The next big challenge is keeping faith in oneself and in one’s work. You learn to read rejection letters very subtextually for any encouragement you can find in them. You also learn to dismiss the “overnight success” stories the media are so fond of peddling and look for inspiration in writers like Carol Shields, who didn’t see success until she was in her forties. Overnight success is a great story, but it never happens in the arts.

How have you changed as a writer over the years?

I don’t think of it as “changing as a writer” so much as it’s a process of discovering who you really are as a writer. The Copernicus Avenue stories are a case in point. Some people are lucky and they know right away—very often these are writers not-so-lucky people who’ve experienced some early trauma that’s forced them to grow up in a hurry. That wasn’t me. I spent the early part of my career trying to write like the writers I admired coming out of university—wildly experimental twentieth century writers like Burroughs, Beckett, and Woolf—until the writer-in-residence at the Toronto Public Library (M.T. Kelly) told me that the aspects of my work he liked had nothing to do with the writers I said I admired. Kelly put me on a strict diet of American minimalists and realists like Carver. Stylistically, that’s when I began to find the voice that would animate Copernicus. By the time I started to write those stories, my motto had become “Don’t be clever, don’t be cool, just tell the f***ing story.”

But finding the stories that are yours to tell can take time. I couldn’t possibly have written about my Polish heritage when I was in my twenties. The stories were staring me right in the face, but I didn’t have the maturity or the detachment to write them. At the time, it felt that they didn’t belong to me—they belonged to my parents. Writing the unsuccessful stories is what prepared me to write the ones that I felt I was always meant to tell. And it’s an ongoing thing. Now, I don’t necessarily feel that I’ve “found my voice.” It feels more as though I’ve penetrated the outer layer of what I’m meant to do as a writer, that I’ll keep changing as I go deeper.

A Grandfather’s Monologue

If you’re not careful, too much pomelo will give you the runs, but the leaves of the tree make the sweetest tea. The day before you want to drink, cut leaves from the tree. Dry them on the roof, under sun. Next day, steep them, then leave the tea to cool. My grandmother would make it for me, as a child. She lived alone, I visited her sometimes, she really loved me. I was the only grandson, not like the others, I was blood for sure. Blood, for sure.