BODY #2 Wherever I go, it is my transfer point. Citizenship is like a sports trophy. It gives you access to benefits. You get to use the spa, the clubhouse. Membership. You get connected with people who might offer you wealth. Canada is not my destination. Because my destination is gonna be somewhere much more magical than this. But I have a thing for trophies that give me VIP membership. ACCESS. If access is for all, I really don't care about how my passport looks like. But when itʼs not, whenever I cross the border, I am put into a box. What is your citizenship? Hong Kong. Illegal immigrant. What is your citizenship? Canada. Model minority. What is your citizenship? Um. I hold a British National (Overseas) passport? British wannabe. Yes. I am the colonized trying to be the colonizer. As a teenager living in the British Hong Kong, I had an obsession with the United Kingdom. My favourite bands were Blur, Pulp, Suede, and Radiohead. My favourite actors were Jude Law, Daniel Day-Lewis, and Christian Bale. I had a total crush on him when he was twelve playing Jim Graham in the Empire of the Sun. I watched it twelve times throughout my life, I believe. I suppressed my love for Leonardo DiCaprio even after Titanic because heʼs American. And as far as I understood as a teenager, Americans are jerks. Nobody is truly proud of being American, other than the white Americans. I bought Reeboks sneakers with the British flag on the shoelace plates. My favourite accent was the British accent, and I still find it hot. I didnʼt know nothing about the politics among England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. But there was one thing that I thought they had in common—“they are all really cool.” My favourite brand of cookies was Walkers Shortbread. My favourite musical instrument was the bagpipe. You know that song Scotland the Brave? I almost got moved to tears every time I heard it. As if I found my roots. And I still have some of those feelings nowadays when that memory is triggered. But now I have to first relive the experience of admiring the British. And then remind myself of why I admired them. And then I try to unlearn that idea without invalidating myself too much. But most of the time, Whenever it happens, when some random Scottish guy in a kilt decides that he should play the bagpipe on the street in Toronto, I still allow myself to indulge in that sense of prestige. Being British is not in my blood; itʼs in my head. I heard that the British were the worst people, historically speaking. But whatever that means, they still have a special place in my heart.

excerpt

Strangers

Prelude

Toronto 2013

Mariam Ali found herself staring into the very eyes of hatred. They were a chilling and vibrant blue. A colour so crisp and cool, it reminded her of the fresh breeze that kissed her cheeks when she opened her window in the early hours of dawn. She marvelled at how a shade so cold, could burn like fire, almost as if it were searing her very skin. There she stood in the middle of an alleyway, held down against a metal fence by a man twice her size, wearing a ski mask. Yet here she was analyzing the colour of his eyes. It was absurd, almost comical really.

The grip he had on her throat tightened, and for a moment she thought perhaps he wanted to squeeze the life out of her, but all too quickly his hand relaxed and instead he lowered it to the lining of her headscarf. He toyed with it for a bit and then began tracing it till he reached the pin that was holding it all together.

She stiffened suddenly, and he smiled wolfishly at her reaction. It was a grin that lacked warmth, a baring of teeth to show that he was pleased in making her squirm. To her horror, she felt a burning sensation in her eyes and her vision grew blurry. “Don’t you dare cry,” she chided herself.

Leaning closer towards her ear, he whispered harshly. “Are you scared? ”

Mariam’s mind whirled, as she remembered the last time she was asked that question. It was from her Islamic teacher of seventeen years, Muftiyah Fatima Hassan. At the time, she could hardly answer her question through the blubbering of her tears, so her teacher took the liberty in answering for her.

“You cannot scare the one who fears Allah,” she said gently. “For when you shove a gun in their face, or hold a knife against their throat, they don’t see death. They see Paradise that will relieve them of their temporary Hell.”

At the time, her words held no meaning for Mariam, and the confusion she felt seemed to only make her cry harder. Even now, as she stood in the very situation that Muftiyah Hassan had described, Mariam realized she was scared. Her heart pounded thunderously against her chest as if it was knocking on the door of death itself. Her breathing grew shallow and rapid as her skin broke out into a sweat, that somehow made her feel hot and cold at the same time. The howling and screaming of her thoughts banged against the walls of her skull and yet she could produce no sound.

Scratch that. Mariam wasn’t scared. She was petrified. Terrified. Gripped by the icy realization that one brief instant could change her entire existence, granting her a one-way ticket to the land of the unknown. The land of the dead.

To where, she would meet her Maker.

“Allah,” she thought sadly. “Is it bad that I am scared? ”

For a moment she could only pity herself until suddenly it dawned on her.

“I am returning to my Maker,” she thought once more.

An abrupt wave of emotion washed over her, the strength of it making her gasp in shock. The tears that had clung to the surface of her eyes, no longer resisted and they streamed fiercely against her cold cheeks.

She was returning to her unseen friend, Allah. Her Al-Waddud—loving friend. Her Ar-Rahman—merciful friend. Her Al-Waliy—protecting friend. The only one who had stuck with her since the time of her birth. Mariam was surprised that this time, it wasn’t fear that she felt, but relief.

She could feel her lips stretch into an almost stupid like grin and suddenly she laughed.

“I must be crazy,” Mariam thought as she snickered. Who would laugh in a moment like this? The shock of impending death must induce insanity.

Although she couldn’t see his entire face, Mariam noticed the gaping of his mouth, in what only could be dumbfounded shock. It seemed to only make her laugh even more.

He still had a good grip on her and his hand returned to her throat as he slammed her into the fence. She winced as the jaggedly sharp fence, poked and prodded her back.

“Why are you laughing? HUH? ” her attacker shrieked. The blue fire in his eyes danced as they narrowed in anger, his lips pulling back into a snarl. “What the hell is so funny? ”

Mariam could hardly answer. She could still feel it, the magnitude of happiness. The sheer consciousness, and awareness of Allah’s presence. He was there and He would take care of her. Just like He always had. A feeling of love seized her heart so strongly, terrifying her, so much so that she trembled.

“You cannot scare the one who fears, Allah.”

For the first time in a long time, the void in Mariam’s heart ebbed away. The space was too full; crowded with emotions that she couldn’t even describe as the thunderous pounding of her heart slowed. Her tears disappeared as swiftly as they had come. She felt light, drunk on a sensation of freedom.

Her once slack spine suddenly straightened as she cleared her throat. Looking right into the eyes that had mesmerized her only moments ago, Mariam responded to her attacker’s initial question.

“Scared? Of you? Not in the slightest.” Her voice ringing clear and loud into the night air.

She was astonished at the vitality that came after feeling so fragile. It was a confidence that she never had felt the likes of before. There was no room for fear in her heart for man, when she was filled with love for her Lord.

“You cannot scare the one who fears, Allah.”

She felt it. Felt Him. Felt His Might and Strength, as her entire soul reached for it, clinging onto it desperately.

For the first time, since he had grabbed her, her assailant grew angry.

“You liar!” he snarled as he gripped her throat, slamming her once again into the metal fence. Her answer wasn’t what he expected. He wanted her to cower. To go on her knees and beg for life.

Instead, Mariam fixed him with a cool gaze of defiance.

He blinked for a few seconds, before removing one of his hands to reach for something in the giant pocket of his coat. Even in the dimly lit alleyway, Mariam recognized the distinct shape of a handgun. It was the first time she had ever saw one up close.

Pressing the cold muzzle against her abdomen, her attacker asked, “What about now? ”

Shade

Dad plans to bring me to the Baracuda, the bar he used to own.

“Are you sure you don’t want to come out with us, Mom? ” I ask one more time before we leave. “We don’t need to go to the bar. We can go somewhere else.” After hearing the consequences of Dad’s drinking from Paring, the prospect of spending time with Dad in a bar is daunting.

“What do you mean? Of course we have to go to the bar,” Dad says. “Don’t you want to see the Baracuda? It’s my handiwork, after all.”

“Of course, but how about Mom? ” I ask. “We can just stay in together.”

“Really, princess? ” Dad asks. “You’re in Boracay and you want to stay in? ”

It doesn’t help that Mom’s already turned the TV on to Little Sister – the Philippine version of Big Brother—and the reality show brings back all the mediocrity of our life in Canada. It’s depressing to think of amidst of this luxury.

“Go on,” Mom says. “It’s good for you and your dad to spend some time together. Just don’t do anything I wouldn’t do.”

“Then we wouldn’t be doing anything at all,” Dad says, but eases his comment with a kiss. “Don’t worry, darling. I’m just showing Benni the sights.”

*

Inside the bar, hanging cloth lanterns tie-dyed pink, blue, and yellow provide dim lighting for the small space. The lanterns serve as the only other company besides the bartender. The bar’s walls are panelled with chalkboards boasting the number of shots guests could down in a row.

Dad points to his name on the wall. It’s faded and dusty, but still there for anyone to see.“It says I could do twenty-five here, but in truth I can do at least thirty. I was going easy that night.”He approaches the bar. “Hoy, Chris, two tequilas for my daughter and I, and a B&B each to chase it down.”

“Dad, I’m fine. Just a coke for me.”

“A coke? ” Dad asks. “You’re coming to my bar and getting only a coke? ”

“Why not? You can get one too.”

“Are you kidding me? This is our night together, princess.” When I don’t respond, he asks, “Have you ever even tried a Bénédictine and brandy? ”

“No. I can’t stomach brandy,” I say.

Dad lets out a hearty laugh and hands me an ice-filled glass topped up with a rich amber liquid. “Take just one sip,” he says.

“I’d really rather not. How often are we out together, Dad? It’d be a shame to get drunk.”

“Drunk? Whoa, princess, who said anything about getting drunk? One celebratory shot and a glass of B&B will not get us drunk. We can go after that.”

Dad’s words are so earnest, and his look so genuinely eager for us to spend time together, that I wonder what harm one drink could do.

I cheers Dad and we down the tequila followed by the B&B. Both drinks burn my throat and numb my tongue, but the B&B leaves a rich taste behind that lingers on the roof of my mouth.

Dad laughs as I cough.

“Dad, that’s the foulest chaser ever.”

“We can get you a sweeter one.”

“No. No more shots and no more chasers. Let’s go and see the sights.”

“What’s the rush, princess? The night is young. Besides, I want to chat with Chris for a quick second, okay? ”

I sit by as Dad asks after the wellbeing of old friends and business connections. I sip my B&B, growing accustomed to the taste. Chris keeps Dad’s glass topped up as they talk. I can’t keep track of how may top-ups Dad’s had, and Dad brushes off my entreaties to go until my hearing has grown dull and I realize with a start that I am beyond tipsy from my far-from-watered-down drink.

I get up, surprised to find I can hardly stand. Friends in Canada used to tease that I was a cheap drunk. I used to boast that it saved me money, but I regret it now.

“Dad, we should go.”

“Go? ” Dad looks at his watch. “Princess, it’s only 10:30.”

Despite the number of refills Dad has had, he looks more sober than ever, albeit with slightly more rosy cheeks. In that moment, I hate myself for not paying enough attention, and even more for wanting to leave.

“How often do we get a night out like this? ” Dad asks for the fifth time tonight.

The statement is so true that I want to cry. I take a deep breath, nod, and sit down, determined to cut myself off and monitor Dad. As soon as I sit, though, Chris refills my glass.

Dad holds his glass up for a toast. “To being here. I’m glad you’re here, princess. I’m glad we’re all here together.”

“For sure. We haven’t done this in a long time. We hardly ever see each other anymore.” I’m still sober enough to see how my statement subdues Dad—the sides of his mouth tip down and a look of dissatisfaction crosses his face.

“Aren’t you going to drink? ” Dad asks. “It’s bad luck not to drink after a toast.”

I take a small sip and, not wanting to ruin the night further, change the topic. “It’s nice being here, Dad. I’m learning a lot. I never knew about Sarah, for example. Talk about an oversight.”

“An oversight? ” Dad laughs. “What do you mean? Why would I tell you about a girl I used to date? ”

“You always talk about girls you used to date. You just told us about that chick you crashed your motorcycle with.”

“Oh, but she was nothing,” Dad says.

“Unlike Sarah,” I say.

“Unlike Sarah,” Dad says. “For a long time, Sarah was everything. I really did love her. I didn’t feel right for a long time after we split up. Heartbroken, y’know. The word’s not a cliché for nothing.” Dad shakes his head and looks at me. “Are you seeing anyone, Benni? Anyone I need to carry my shotgun for? ”

“Dad, you know the answer to this already. I was seeing Tom.”

“You guys split up ages ago. You’re not seeing anyone new? ”

“We split up three weeks ago, Dad.”

“Tom was nothing though. You dated for all of two months, didn’t you? ”

“I wish. We dated for two years. I only thought we were going to get married. I’m only a bit heartbroken.” I laugh, trying not to sound self-pitying, and take a gulp of B&B so I don’t have to talk more.

Dad snorts. “That guy? You never seemed to like him much.”

I choke on my drink. “Are you kidding me? Tom was great. He was a lot like me, and he made me feel like I belonged.”

“Princess, you have no problem fitting in. You don’t need someone to help you belong. Let’s be honest here; what’s really bugging you? ”

I stare at Dad with glazed eyes, trying to focus. Something he’s said has stood out for me—one of those moments where you want to pull out a pen and put an asterisk beside it. I’m trying to puzzle it out long after Dad’s lost interest in the conversation and ordered us a second round of shots.

I study my father’s face, taking note of the greys peppering his hair that I hadn’t noticed the last time I saw him—a long time ago. I don’t have the heart to say that I finally realize I’d been trying to fill the gaps he’d left—the sense of not belonging he’s given me, and the feeling of never being enough to stick around.

I leave the bar when I am finally too drunk to speak. I stumble out onto the sand, blinking as though the millions of faraway stars are too bright.

I ask Dad to join me, but he tells me to leave without him. He wants to stay and beat his personal best.

I don’t turn to say bye when I go. I don’t want to see him sitting there with his sandy toes clutching tight to the weathered bar stool, his heavy arm and moistened palms nursing a sweating beer bottle, his eyes open but seeing nothing.

At that moment, I prefer to see nothing too.

The sea is only a few strides away, but remains unseen beyond the light of the bar’s front door. I stumble towards our suite. Occasionally, I veer too far to the left or right. On one far detour left, I feel water on my feet. The sea, which barely touches the tops of my toes, lies before me in an unseen sheet of blackness. I could be standing in tar—that’s how dark it is.

I wade out into the darkness, seeing nothing and feeling only the clothes on my skin and the wet sand under my feet. I keep wading. The water doesn’t reach any higher than my calves. At one point the land dips and I wade in beyond my knees, but soon it levels out and I remain ankle deep.

I spot a white blur in the water and approach it, drunk and without fear. It’s a white buoy, which during the day is too far out to see.

I gaze around. “The tide’s gone out,” I say to no one in particular. “I’m standing in the middle of the ocean.” I look around again before lying down on the sand. “I’m lying in the middle of the ocean!” I yell, my voice thick with alcohol.

The stars are infinite from this position, studding the sky as far as I can see. The water is warm from the day’s sun; it washes into my ears, cradlesmy neck, and fans my hair out beneath me. I imagine this spot in the day—hundreds of meters below the crushing waves. I’m usually scared of the ocean, and I shiver imagining the water returning to bury me the way Moses buried the Egyptians as they crossed the Red Sea.

But here, Dad and I soared well above the tallest tree on the island, and now I lie on the ocean floor.

Here, I am invincible.

*

I return to the resort well past midnight, still tipsy and dripping wet from my rest in the ocean. Our resort’s section of the island is populated with older tourists who sleep rather than party at night. The effect is one of eerie silence, as though Boracay has become my own personal island in truth.

To amplify the feeling of seclusion, our building is the only one lit along the surf, standing out amongst a sea of shadowy black as though to beckon me home. As the light washes over me, I watch my white shirt and pale limbs come into being from the shadowy, far-flung world.

“Home, sweet home,” I mumble. “It was a good night.” I think of Dad sitting alone at the bar, shake my head, and say again, “It was a good night.”

“If you’ve had a good night, you can’t let it end yet,” a man’s voice says.

I look up to find five men. They’re locals, judging from their dark skin and dusty clothes. It’s as if they, too, have just materialized, though I realize they must have been part of a larger group on the resort’s patio that I failed to notice. The light that’s beckoned me forward hasn’t been for me, but for them where they gather. I offer up a polite smile. I don’t know what they want, but the beach has been friendly all night. My beach.

“Hello, beautiful,” the closest man says. His words are slurred, his gait uneven. The other men are similarly glassy eyed, stumbling through a reek of alcohol. I haven’t seen these men at our resort before, though I notice one of them is clad in the tropical uniform used by resort staff. “What are you doing tonight? ” he asks.

Despite my alcohol haze, I realize that I am only one woman among many men. “I’m on my way back to meet some friends,” I say. “I’m expected now.”

“Is that so? Your friends are lucky to be here with a beautiful woman like you. You should join us instead. We promise we’ll be nice—especially to a woman with those legs, those lips, and that—“ he stares at my chest”—dress.”

I see now how ridiculous I am—exposed and unprotected. I am wearing a nearly-transparent shirt, clinging skirt, and am standing on a dark, empty beach where foreigners keep their windows closed and shuttered. My beach? Ha. Their beach.

I cross my arms over my chest.

“What are you doing? Why are you covering yourself? You could be a real artiste. The only question is: can you perform like one? ” He winks and I remember what Mom said about the country’s movie stars: they’re beautiful, but whores—all of them.

He steps forward just as someone yells, “Stop!”

Dad strides past me and plants himself between us. “What do you think you’re doing? ” he asks.

The man pauses, confusion and resentment on his face.

“Do you know who this girl is? ”

The other men start backing away.

“Do you know who I am? ” Dad yells. “Benni, go upstairs,” he says to me.

Though he’s well outnumbered, I know he’ll be okay. His tone commands authority.

The men hear it too, and the leading man’s resentment gives way to worry.

I slip unmolested towards the resort, though I have to pass the men on the patio to go upstairs.

Dad singles out the resort’s staff in the crowd. “Your boss is going to hear about this,” he says, pointing at the man, whose brow beads with sweat upon realizing we are customers at his resort. “That’s right. If you come back, I’ll have my men on you. Scram! Don’t mess with the King of Boracay!”

*

“And then he said, “Don’t mess with the King of Boracay!” and the men ran away.”

Dad sits proudly beside me. The night’s events, in the sun and heat, feel like nothing more than a dream.

“Dad, you’re my hero,” I say, pretending to swoon.

“The King of Boracay? ” Mom asks. “What if those men pulled out knives? ”

“But they didn’t,” Dad says. “No need to worry, Mother Superior.”

“Or what if someone had a gun? ”

“But no one did.”

“Or what if they come back? ”

“But they won’t. Relax, Maria, it’s our final full day in Boracay”

“It’s comforting that you’re so confident, your grace, but why was Benni alone in the first place? A young woman, foreign to the Philippines, who has no understanding of the language, and has never been to the island before. Why was she alone in your kingdom when she was supposed to be out for a night with the king? ”

“I . . . ”

“You what? I would love to hear your answer.”

“I was . . . ”

“You were what? ”

When Dad doesn’t reply, Mom stands up.

“You’re lucky those men were probably just as drunk as you were. Idyota,” she mutters as she leaves.

Sissy

1.

Sauntering down Aisle 6 at the 24-hour Dominion grocery store, Lee is cradling an overly large zucchini. It sits inside the sleeve of his thick pea-green parka, where he is pretending to house a broken limb. He conjures the cast’s hard shell and the way he’d have to lay on the couch watching daytime TV instead of dishwashing for eight hours at a time. He considers breaking his elbow, a swift snap. Then it wouldn’t be a lie.

Lee has a strange relationship to the truth. The truth sticks her tongue in his mouth obsessively. She runs her hand up his leg, almost, whispering, Why are you shoplifting a zucchini, you fucking idiot? Lee suspects he has latent Tourette’s, what with these voices coming in sharp spurts, accompanied by a shudder or a shoulder tick.

Lately the truth is too much. Last week, there was a staff party at the restaurant. Everyone got too drunk. His girlfriend Linda was throwing up in the bathroom downstairs in the basement for what seemed like hours. Kevin, the other dishwasher and Lee’s sometimes after-work friend, disappeared. When Lee finally found Linda, she’d been hit in the face, her dress torn. She couldn’t tell him what had happened until the next day, and it was all in pieces. She kept saying, It was Kevin, but it was more like a Kevin imposter. He was a monster. I kept pushing him off me, but he wouldn’t stop.

Lee brushes away the truth’s impalpable hand, walks towards the front cash.

“The worst thing is the itching,” he tells the cashier, a bottle redhead, who nods sympathetically as he pays for a pack of cinnamon gum.

“I broke my wrist last year. It sucked,” she says. Lee feels a slippery worm of guilt sliding down the back of his throat. The woman shifts from anonymous cashier to someone with bones that can fracture and heal. He slides the gum in the back pocket of his fading black work pants.

Sometimes Lee uses a crutch. Once, a fake wheelchair stolen by his older brother Dan to use for scams.

Tucked in his Y-front briefs is steak wrapped in Styrofoam. In his right boot is powdered gravy. Up his other sleeve a slim candy bar, for good luck. Always take something from right up front if you’re going to bother.

Lee comes from criminals. “It’s in your blood,” Dan told him as a kid. “Forget working class, we’re thieving class.” He’d pump up his chest, throwing Lee over his shoulder like a sack of potatoes while Lee kicked and giggled, yelling, Let me down! Put me down! Stop! Before Dan finally laid him out on the grass of their yard and tickled him until he yelled Mercy!

Lee still shoplifts on occasion, but he doesn’t do anything else illegal. He has vowed to stop stealing as soon as he makes an annual income above the poverty line. He has never hit anyone or stolen money from a person. He is an anomaly in his family, and he likes it that way.

Lee is thin and lanky, almost girly. Blondish hair, shy smile. His voice lilts a little, higher than most men, and he is often called a fag because of this. Miraculously, despite his femininity, he has never been beaten up or fought anyone. As a kid, Dan was always around to fight for him, and as an adult, he managed to avoid it. He never wanted to hit anyone before. It was what separated him from the rest of his family—the fact that he could avoid it. He counts himself lucky and always had. His adult life was filled with things he created so carefully: good friends, warm holidays, minimal conflict.

Six days ago, it was as though all of his warmth, all of his luck he lived with, was thrown into an industrial blender. He looked at his limbs and couldn’t tell if they were his. Is this my arm? Drop a dish. You’d be surprised how good it feels. To watch shards of white restaurant plates finish their purposeful lives and get swept away into giant dustbins caked with blackened grease and dirt.

What the fuck is your problem? Eyebrow twitch. He shakes his shoulders around to calm his muscular outbursts.

Lee is trying to look forward to supper. George and Stephanie invited him over to get away, out of the house. Steph will bake something weird like a buttermilk pie. She’s very Little House on the Prairie right now. She’s declared a household embargo against beer and pizza, and has taken to doing things like making her own crackers and dehydrating her own fruit. She always makes cordial and serves it in tall parfait glasses with silly straws. Exotic fruit cut up in the shape of stars and hearts on the side of the plate. She likes presentation. She has a lot of fruit scrubs and a lotion that smells like cookies in her tiny bathroom.

George and Stephanie are one of those couples who would shake the foundation of all your beliefs if they ever broke up; a ball of yarn in complementary colours. They have weekly dinner parties with Lee and other friends, but this is the first one since the staff party. They wanted Linda to come, for her to feel comforted and distracted, but she declined the invitation.

The snow crunches underneath Lee’s work boots. Sounds like the crack in his jaw where he holds all of his tension. He walks up Brunswick Avenue a little shoplifting-high, a little remorseful. Mostly hungry and blank. He can’t help wondering when his brain will return, as if it was erased by what happened.

Lee has stopped plotting to hurt Kevin for the first time in six days. Squeeze, or kick, or punch him until he cries. He is trying to make peace with the situation, going against his mother’s suggestion to “kick the living shit outta that waste of skin,” at Linda’s pleading to “just let it go.”

All other days have gone as follows:

Bring Linda breakfast in bed, wait until it is congealed and she is still staring up at the ceiling. Take it away. Stand in living room with daytime television on for noise. “My Teen Daughter Wants to Be a Stripper and a Humanitarian!” Bring her bouquets of flowers, novelty candy from the store across from Future Bakery, books of poetry from Book City. Remind her to go to counseling appointment, doctor. Shuffle in her mother, her sister, Steph, who is her best friend. Apply arnica to her bruises. Hold her if she cries. She only cries once, usually, before Lee goes to work.

Linda talks. There was a guy in high school, her swim coach. There was a trial, a jail sentence, a school divided. Linda is reminded of it all, and can’t go outside. When the coach went to jail, six months plus probation, she didn’t feel satisfied. Still, people avoided her. Blamed her. When Lee suggested calling the cops about Kevin, Linda said,Why bother. Didn’t work the first time.

Outside is too much. Lee is trying to be a good boyfriend, support her, but he is completely uncertain what to do.

He goes to work at the restaurant and works an eight hour shift dishwashing. Lee calls her on the hour.

“I’m fine, don’t worry so much. I’m just, tired.”

“Do you need anything? ”

“I need you to not do anything stupid. Bye.”

When she hangs up, always first, Lee rests his head against the brown grease-stained wall next to the pinned-up schedule and tries to breathe. Lee’s name is written in red marker eleven days in a row. He has no days off because Kevin quit so suddenly, just didn’t show up the day after the staff party.

Kevin. Lee can’t even think his name without his eyes going out of focus, the dirty floor paneling shifting. Kevin. Lee blacks out all the Kevins that appear on the January work calendar. Out of ink. Tries again with his nail. His nails have grown long from neglect.

He brings the mop water out into the alley to dump and looks up to the third storey window where Kevin lives above the restaurant. He thinks it would be too easy, to walk up the stairs, break down the door. Instead, Lee goes back into the kitchen, where every move his body makes feels leaden and irritating. When he thinks there may be a lull long enough for a smoke break, another table clears, another grease-caked pan arrives.

After punching out, he declines invitations to go next door for pints and pinball and instead climbs up the fire escape of Kevin’s building.

He watches through the window. Kevin’s in red jogging pants and a shirt that says “I Survived the Black-Out 03.” He smokes and flicks the remote. Picks at the knee hole in his pants. His girlfriend sleeps on the armchair. It’s the same every night. Stops to roll joints on a TV guide. Eventually falls asleep. Lee looks for signs of distress in his face, guilty dark bags under his eyes. Finds nothing.

Lee goes home when a woman startles him, walking through the alley muttering to herself. He notices his fingers are numb, and he’s lost his nerve. If there was one thing valuable he learned from his brother it’s that you don’t want to go to jail. The voices of reason beat the voices that chastise and degrade.

2.

Stephanie is doing pretty well, considering Linda is her best friend. George is one of those people who deals with tragedy very calmly. He has been writing letters to the community paper about safety for women in the neighbourhood. He has been examining his life and begun using phrases like “I’ve been noticing my male privilege.”

George has never seen a crime that he wasn’t watching on television. He thought it would feel different, that it would feel monumental. His own composure scares him.

Stephanie is all life goes on, and it coulda been worse, and she’ll heal and move on.Steph had a gun in her mouth during a hold up at the Cash Mart, a father who locked her in a closet for three days, and scar in her left foot where someone once stabbed her when she bartended at a strip club.

When Lee arrives for dinner at the apartment that Stephanie and George share with some other kids from school, she notices his TV-dinner eyes. His complexion is an old dishrag.

“You look good,” she says, giving him a friendly hug. Stephanie regards her position amongst their peer group as Den Mother, emotional glue stick, party starter, and conflict mediator.

Stephanie watches silently while Lee reaches into his pants, pulls out the steak. She grabs his red offering and smiles warmly, careful to hold his gaze, hoping to transmit some comfort. She’s worried for him. He doesn’t seem right. Even though she knew he was sensitive, erratic, a soft little boy with the exterior of a lanky slacker comic book artist.

She sits Lee down on the couch and runs her hands over his head before going into the kitchen to bring out a tray of lime cordials. George is finishing up a PlayStation game while Stephanie tells Lee about her latest art project embroidering internal organs on the outside of cowboy shirts.

Lee seems pretty calm, considering, being around his friends.

“So, Linda doesn’t want to come eh? ”

“No.”

“I made buttermilk pie—her favourite.”

“Yeah,” Lee says, shrugging. “She’s still taking those sleeping pills the doctor gave her.”

The dinner table is set with a frilly lace tablecloth and fancy china Stephanie bought at an antique sale two weeks ago. A plastic pitcher with Strawberry Shortcake is filled with strawberry daiquiri. “My latest eBay conquest,” Stephanie says, filling the metallic pink pint glasses with the pulpy liquid.

All three take bites and chew methodically. When they are done, George clears the dishes away and Stephanie prepares the pie and ice cream.

Lee says it first.

“I want to hurt him.”

Stephanie says, fork clinking on china, “I want to kill him.”

George raises his eyebrows a bit. Closes his eyes tightly, turns red. “We could probably get away with it.”

Anna, their cherubic roommate walks into the kitchen, mumbles, “Hey.” She looks like a commercial for facial cleanser. She goes into the living room and turns on the television. The sound of The Simpsons fills the apartment. The one where Maggie shoots Mr. Burns.

“I love this one,” they say simultaneously, getting up and heading towards the other room.

3.

Lee goes to the bathroom and throws up. George watches TV with Anna. Stephanie chain-smokes. Lee watches the swirls of former pie turn and he thinks he might faint. He rests his head on the toilet bowl, snivels, squeezes his eyes shut.

What am I supposed to do with this? How can I live with this?

The truth climbs up his spine, says, You’re just going to have to.

Lee knows that he is the worst person to ever live. He hadn’t fully believed it before. He protested vehemently his own self-worth. But here it was, staring him in the face while the creamy vomit swirled down. Like his mom used to say, “You’re fucking nothing.You sissy little shit, you’ll never be anything.”

The memory of his mother’s voice sometimes sounds like the truth, the same soft woman, insistent and composed. It confuses him. He heaves again.

Leaving the washroom, George hands the cordless to Lee with an anxious look on this face. Linda says, “I hear something outside. I can’t breathe.”

Lee grabs his coat and runs out to the street, keeps a steady pace the whole two blocks home. He climbs into bed with her, still wearing his parka and sloppy snow-covered work boots. She is staring at the ceiling. He holds her and falls asleep there, dreams about eating fish sticks made from dead prime ministers. When he tells Linda about the dream, it’s the first time he’s heard her laugh since it happened.

The next day Lee comes out of the kitchen at work, wipes his wet, pruned hands on his apron, and walks to the bar to have a smoke. George is sitting there nursing a pint, “Hey, I was waiting for you to take a break. Come with me.” He takes Lee by the arm, weaves through the tables, and out into the street, even though they are both wearing T-shirts and the snow melts on their pale arms. He stops three doors down at a storefront window. Looking in they can see a self-defense class in session.

“I’ve been watching them for an hour,” George says. “And I think I know how to do it, how we could really fuck Kevin up, you know, make him pay for what he did.”

“Are we going to kick him in the groin until he dies? ” Lee asks, laughing. Inside, a sweaty blond in a ponytail is kicking a padded person that looks like the marshmallow man from Ghostbusters.

“Well,” says George, who is even more girly than Lee, more timid and non-confrontational, has never so much as landed a punch, Lee guesses.

“We need Stephanie,” Lee says.

They run around the corner to George and Steph’s apartment. Stephanie is doing crunches on the living room floor, listening to Michael Jackson’s Off The Wall.

“How are we going to do it? ” George says, panting.

“Why aren’t you guys wearing coats? Do what? ”

“Kill Kevin.”

She sits up, takes the small pink towel from around her neck and dabs at her forehead.

“What the fuck are you talking about? I just said I wanted him dead. I didn’t say I was going to kill him.”

The boys sit down and light smokes. Rub their numbing arms with couch pillows.

“Isn’t your break over? ” George asks.

Lee is startled. “Holy shit, I forgot I was still working!”

Lee runs out the door and crosses the street moving fast into the parking lot, ducks into the back door of the restaurant. A backload of dishes, resentful looks from the waiter who hates him. He feels energized, like maybe something will happen, maybe they can make Kevin feel some sort of forced empathy for what he did. They don’t have to kill him, just fuck him up a bit. Like a beat down. Like in rap videos.

Kevin is waiting outside in the alley when Lee goes out to dump out the mop water after closing. His face is a blank glazed donut. Lee feels cheated, that this wasn’t what he planned.

They stare, a foot apart, like two cowboys in a standoff. Kevin starts to speak, “Look, Lee, I don’t really remember everything, I was so wasted, man.”

The crowd in the bar next door cheers after the Leafs score a goal.

Lee’s heart is the only thing he hears. His mouth is dry. He lifts the mop out of the bucket, slopping water all over the pavement. He pushes Kevin up against the brick wall, pins his chest with the mop handle.

“You don’t remember? That’s your excuse? ”

Instinct takes over. It must be in his blood, this violence.

Walking through Glass

2010

I never knew what condition my mother would be in when I arrived at the hospital, if she would be lucid, sleeping, in an altered state, or maybe even gone, dead.

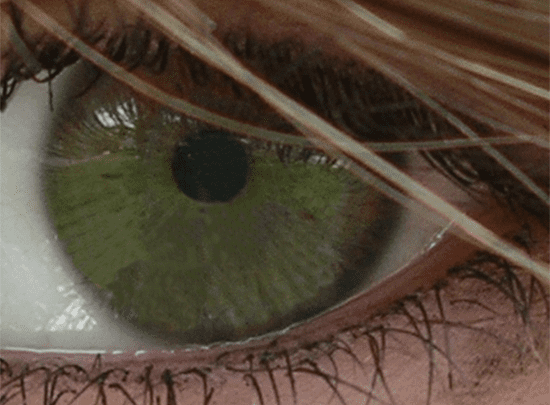

While snow melted and everything was slowly coming to life, my mother lay dying. I finished my cigarette outside, squatted on the ground in the grass. I cried and smoked and touched the grass all at once as if it were the fur of a sleeping cat. There were permanent dark circles set under my green eyes. My fingertips were yellow with nicotine where I chewed the skin from nervousness. Even the sky seemed scattered and uncertain as if the Spring sun might disappear and a storm might crash in.

“Are you okay? ” asked a woman who approached me in a gray suit, everything perfect and in place, stockings, heels, and a pearly face with red bold lips. I squinted, shielded my eyes from the light like a vampire as I looked up.

“My mother is dying,” I said with the sound of apology in my voice, still touching the earth with my other hand. I had forgotten that people could see me, and this stranger standing above me reminded me of human connection. I needed to tell someone in that moment and the woman in the gray suit would do.

“I’m sorry,” she said softly and walked away.

I stood up from my patch of soil, put my cigarette out with my shoe, crossed the street, went through the revolving doors and back up to my mother’s room. On the way up in the elevator I put a piece of peppermint gum into my mouth, fished my shades out of my pocket and put them on. It took forever to get to the seventeenth floor, an elevator crammed with patients in gowns and bandages holding their IV poles, or visiting guests and doctors. We all knew someone with cancer in this hospital. Some of us were here for those in the beginning stages of the disease with family members or friends newly diagnosed, in treatment or having surgery. Then there were people like me, the disheveled and overtired, the ones who looked like we hadn’t left the hospital in days, on constant duty, not wanting to miss the end, scared to go to the bathroom or steal away for a smoke, just in case.

The palliative care ward was quiet. My sisters were outside our mother’s room talking in whispers. They traveled from Montreal and Vancouver to say their goodbyes to our mother who had slipped in and out of consciousness over the last three days, almost in a coma, her eyes glassy, hollow, her body bruised from multiple needle entries from IV fluids, morphine, saline.

The rooms of the dying were small and sterile with no color, just bodies, wires, oxygen masks, gray speckles in the floor. I entered and sat beside my mother’s bed, where I had covered the walls with images of the natural planet, perhaps it was to remind me of my own life and to give my mother something beautiful to look at in her own quiet moments alone. Maybe it would calm her or maybe she could imagine herself in the images themselves, in Africa with animals, or by the edge of a cliff, or winged, able to see from a bird’s eye view.

Sometimes mother and I would stare into each other’s eyes as if we were thinking or feeling the same things, looking for a way to speak to each other, the pauses filled with a lifetime of stories desperate to come out, but now, nothing. She had been in a coma all night and morning. Her eyes were almost transparent, her mind far. I wanted to shake her, to scream at her even, but I knew she was dying and I just wanted it to end, couldn’t bear to see her vulnerable, in fact I hated it, hated looking into those glassy eyes.

My mother’s eyes in earlier times were full of expression, always on the go, rushing to get to lessons, dropping dad off at work, or the looks she gave us girls when she was mad. One look from my mother could silence me. In those days mother had long curly hair, round beautiful green eyes and a sharp tongue. When she was mad, all she had to do was look at you and you would know to shut it, and sometimes she might eke out a tiny phrase like, “If you even dare,” or one word, eyes like darts: “Don’t.”

But now, now her eyes were dull, heavily lidded from the months of morphine, chemotherapy and radiation treatment, now she was bald and her power nearly gone.

Author of the Month: David Layton

Tell us about yourself.

I have a book coming out next year with HarperCollins called Kaufmann & Sons. I teach at the creative writing department at York University and also do some work with the University of Toronto through their Continuing Education Department.

When did you realize you had a passion for writing?

I grew up with writers and poets and that should have inoculated me against any desire to write. Unfortunately, I sat down and wrote a novel just after I turned 20. It had something to do with wanting to impress a girl I was dating. We broke up some point after I’d written the third chapter and by then it was too late to stop.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

The first book I truly loved was a Bitter Lemons by Lawrence Durrell. It’s about the Cypriot revolt against the British in the 1950s. At the time I didn’t really know the British had even been in Cyprus but the book made me feel as if I did know, and that made me feel wise. I learned that that feeling was the gift of a good writer.

How and when do you find time to write?

If you go looking for time you’re not going to find it. I force myself to write every day for three hours. I’ve also learned to be wary of any inspiration obtained at 2 am, so I work in the morning.

What has been some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced as a writer?

Procrastination, laziness, fear of failure. These are my three Horses of the Apocalypse.

How have you changed as a writer over the years?

I’ve developed a few grey hairs.