Helium rainbows, romantic drums, Buzz Lightyear going boldly to Sesame Street, Garage bands, trees, pink choo-choo-trains, Elton John fiddles a tea party of spring. But, alas, this vision falters. Teachers! Calling reprimands. Clapping beavers, Forcing constant repetitive skills. These random words, awkward turtles, In a flash are sent to West Mabou. But hark! This injustice is over! Students prove the teachers wrong by calling War! War! Fight the power! Ireland, Scotland, Canada— The drums! A screaming sentinel shrouds his comrades, A shifty servant of espionage. First brother horse sees the message: A round of simpletons approach. But this convoy is a mere distraction. Pianos, as Beethoven, filling outer space! The keys are fired and in a flash, An orchestra of lasers signifying pain. The rebels fire their sugar cubes; Gymnastics of the underworld, fragmented with pins. As this tragic square dance begins, The world of children is banished forever.

Shorthand

Growing Up in the Suburbs of Toronto

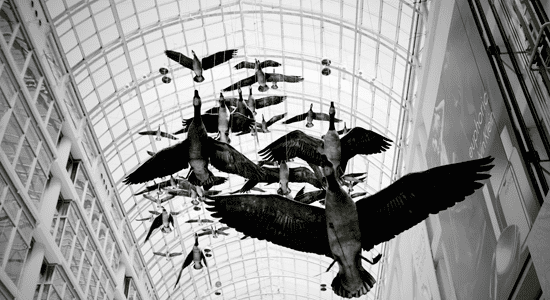

Growing up in the suburbs of Toronto my earliest memory was taking the transit downtown I remember begging my parents for a window seat on the bus, a small hand against the dirt-ridden pane catching my fading reflection staring back street lights being blinded by the sun I remember the elevator up the C.N. Tower My heart against my chest and parents’ smiles, and standing on the glass floor looking down at people tinier than me walk by. I remember being scared, of something I didn’t understand. I remember the ferry rides to Centre Island waves in the lake smaller than me, slipping under the boat me rocking the boat, rocking the lake. I remember the Eaton Centre, as it swallowed me whole, and how it surprised me to see, all the legs their feet and their shoes sandals and slippers and I remember looking up, through the glass ceiling, (as the sun’s rays cascaded through and through) at birds that sailed on a higher plane. I remember the cold water of Lake Ontario, and swimming out, while my parents got in only shin-deep and stood the size of my thumb. I remember beads of water, some easing off my face others resting and the waves cradling me to and from shore. I remember the stars— little bulbs that God switched off when the sun came up— and I remember the moon, still made of cheese. I remember flashes of the subway (and eyes closing) and the bus (and eyes closing) my feet moving my mind frozen (and eyes closing) being wrapped under the blanket, the cold comfort of the pillows (and eyes closing.) Today, I remember everything as it moves to my peripheral (eyes closing) and I rush like after busses at their stops and trains at their stations to write it down (eyes closing) because tomorrow’s a new day and tomorrow I might forget. Eyes closed.

Descriptive Exercises

I’ve often picked up a stray object, tossed it into the middle of the room and asked participants to write in response to it. In one case, it was a lost glove I found on the sidewalk. It’s fascinating how a found object can evoke the physical and emotional attributes of the person who lost it, and their personal history.

I also like to ask participants to write about “home.” What is it, where is it, what does it look like, how does it feel to be there—or not be there . . .

Death in an Evacuation Camp of One Who Never Saw Japan

When they remembered his death for every year after, every 16th of November, they would remember his face before his wavering eyelids stilled, and his glistening body under the light of the kerosene lamp before its warm sweat lifted up into gentle vapour at its final stirring. Then they would remember themselves on that night cramped tightly around the cot on which he lay. They couldn’t allow themselves voices then and allowed nothing to escape their mouths nor eyes. They swallowed carefully and their hands were stiffly clenched, the skin tightening grittily across bleak bones in their laps. They sat in the dingy outer circle of the single light that flickered and brightened and flickered and brightened and the grey of the woolen blanket covering the lower portion of their brother’s body seemed to seep into their faces as if by osmosis. There it settled until the flame of the lantern shone momentarily at its brightest then again resettled unflinchingly. They could feel, each of them, the grey spreading softly into their complexions, into their eyes and they watched him through a dim veil.

He was still beautiful, they thought, even through this grey. And it then seemed to them that the veil lay delicately upon him now as if tired, suspended dust had quietly fallen upon the black depth of his hair, along the sleek upward slope of his half-closed lids, the slender length of his nose and across all his taut angles. Each fluttering of his lips or eyelids sprinkled up particles, silver and illuminated into the light. They were continually waiting for him to rise to let all of it shift into nothing or back into the neat folds of the blanket. They recalled the occasional rustling of his legs beneath those folds and thought how foreign his beauty seemed at that moment—so still, so reticent, and so unlike the brother they knew. Their Juji, tall, limbs spanning lithe ground, hair waving in the wind, was always in finely-honed motion; even as he stood before them talking his long fingers would gently flex and fan. And when he spoke it was with that same ease of expression, without any fear of striding straight into the eyes of whomever he was speaking to. He always had that engaging Japanese manner of seeking affirmation of whatever he had said. And they remembered always answering yes, that was so. They recalled Juji on the logs at the mill nimbly maneuvering them onto the flume, never once falling into the water, never once falling away from the beauty of his balanced grace. Everyone knew Juji and watched him.

Then they recalled seeing Teru slowly raise her hand from her lap to the lamp to try to adjust its flame so that it would stop wavering. It was old and kept feeding unevenly on kerosene. None of them wanted to see him in those flickering flames when all his pain glimmered across to their faces. They heard once again the sound of their mother’s broom scratching at the ice forming in the crevices of the walls. They saw her staring at the cold corners surrounding her Juji who was dying.

Before he died, his head tilted itself back, his mouth fell slightly open and out of its dark hollow came a strangely ungracious gurgling cough. For that moment they could not recognize him. They quietly remembered the silence that followed. Teru began gently sponging his body with warm water as it could still respond to her touch, her face growing more expressive with each stroke. They remembered the sound of the water splashing against the side of the steel bucket placed near the cot as being a much too everyday kind of sound to settle around a dead person. Their father who had sat for so long, small and old in the dark with Juji’s trousers in his lap, held them in his tense moist hands, crying dryly. For as long as they knew their father, he had always been old but then, he looked still more callously aged. Their hands unclenched bit by bit, their father slowly stopped crying and their mother stared into the corners.

All this they recalled and the thinness of the walls that splintered with each new wave of cold outer wind, the wooden table with its uneven legs ever shifting on uneven ground, and the cold dirt beneath their buttocks. They saw the clear particles of ice ever forming in numb corners of this room. This room, this shack was not to be distinguished from any of those with which it formed a row, and row upon row formed block upon block in a hastily erected ghost town delineated at its fraying edges by many dark strong mountains. This was where they remembered Juji dying and the way they would remember how he must have felt dying here—after having been swept up and aside, and buried among cold mountains hoping not to be forgotten, too afraid to say something to be remembered. It was so much the way they had all felt but kept trying to live past feeling long after they had left the place.

They take out an old photograph every November 16th; sometimes between November 16th’s. They clutch at its corners and renew the bitterness they look for in each of their own faces in the photograph. The coffin lies in the foreground—a mail-order coffin sent for from Vancouver, and they all peer over top of its greyness, black and white faces trying to express a carefully hidden and complex anger that could never let itself be shown in two shallow dimensions.

He was taken in the coffin to a vague clearing at the uneven edge of the camp’s blocks where over and under him his friends placed twigs and dry branches. They watched as the flames began, so orange and intense that they could not erase the grey of the coffin which softly peeked in and around the flailing arms of the fire. His friends kept the flames healthy and burning poking them here and there. They remembered the terrible smell and leaving for their house and finding their father in the dark again with Juji’s trousers. In the morning he left for the clearing with a tin can in his hands.

Juji’s death reminds them all of what he suffered, what they suffered knowing he died so far from their father’s home and so far from his own mistaken home in the half-comforting company of only those as homeless as he. When they look into their worn photograph that is what they see—they see their timidly homeless faces staring up at themselves across their dead Juji’s body in the grey coffin.

This short story was published in the University of Toronto Review when Kerri was a student there. It was the first time she saw her words in print.

Gimme yr little quiet

Anyway, you’re not coming and I can’t have you this evening I have to put the flowers around my own throat and buy myself a film the red seats will be the violets of my lap. I’m going to begin now anointing myself with the oil of your absence. That is this book. And I made the book of you in your absence and I’ll come into the house and in the hot oil of your absence, my anointment a rose-shaped burn at my crown. I'll buy me flowers and cover my chest protecting my health in our violets. I can’t stop but I can have this open and we might communion then right among the spaces : between my side and inner arm, our outer arms, your inner arm and your thick torso and behind that your tight heart and the space between that nut and some energy around which there is no space We dip dates into a good wine and have communion. Have we the same mouth? Sometimes.

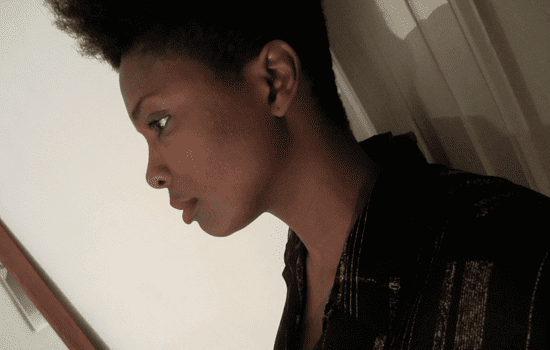

Emerging Author of the Month: Aisha Sasha John

Tell us about yourself.

I’m a poet and a dancer. Both my writing and my dance practices are spiritual practices. As a dancer, my work has recently been exclusively improvised, both without accompaniment and with improvising musicians. I consider my dance a prayer, a sort of exaltation through movement. My first poetry collection, The Shining Material, was published last year by BookThug. In it, I consider what grace is through the use of the self-portrait. The prosody of that book is intended to be a feast and is also trance-inducing. For me, that which induces trance or some sort of quiet space is a feast. Currently, I’m working on a manuscript calledThe Book of You. I’m not entirely sure what it’s about yet (or else I wouldn’t be writing it) but it might be a portrait via a series of letters. I know that in this work I will be asking about what honesty is, and I’m wondering if it might have something to do with desire and one’s comfort with/acknowledgement of various desires. There is a continuing investigation of grace in The Book of You too. Recently, a selection of it was published as a chapbook called Gimme yr little quiet.

Tell us about the piece you’ve decided to share.

This is a poem I wrote while reading some Sappho.

When and why did you realize you had a passion for writing?

I don’t know if I’ve ever “realized I had a passion for writing” much as I realized I had a passion for reading. And that was very early. I think maybe when I first learned to read—and I remember the exact moment—was probably the definitive point. Understanding that the groups of letters on the page corresponded to the words my mother was saying, and thus cumulatively to the meaning of the sentence, of the story, was astounding to me. It still is. It was so good, this reading business, that I wanted to be a part of it too. I wanted to do for others what had been done for me as a reader. And so I did. At this point, I need to write. I can’t not write. But that is because I made it a part of my living. I made it like that by doing it, writing regularly when I wanted to and also when I didn’t want to. The passion, then, is a product of a love for reading and a little bit of discipline.

What pieces of writing/authors have had the greatest impact on you?

This is too big of a question to answer precisely. So I will talk about the first poetry that made me not just want to write but to be a poet specifically—that is the poetry of Mr. Amiri Baraka. That decision was, and is, continually reinforced by the work of great and even good poets, but it was with Baraka that I got that first giddy giddy giddy feeling that manifested itself as ambition. Right now I am having that feeling with response to the work of Edmond Jabès, Aimé Césaire, and Jack Spicer.

What kind of writer do you aspire to be?

I aspire to be the kind of writer who goes and does what she needs to do.

How and when do you find time to write?

I don’t find time to write; I make time to write.